When I visited Florence over the summer, I was surprised by how many Filipinos I met. Some were priests. Others ran restaurants or worked as artists. Hearing Tagalog in Tuscan streets made me think about older connections between Manila and Europe. I began wondering how Manila was imagined by the rest of the world during the early Spanish colonial period, and why Italian culture, in particular, felt strangely familiar to me.

While researching about Philippine amulets, I read Ashley Buchanan’s dissertation where she writes about Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici’s recipe manuscript. In the Archivio di Stato di Firenze, she found a sleeve containing more than two hundred recipes owned by the last Medici princess. The manuscript includes syrups, fever waters, perfumes, paint formulas, and medical remedies. In the middle of these entries, Buchanan noticed a short note on the St Ignatius bean. It lists its virtues plainly: protection against poison, relief from spasms, help in childbirth, and defense against unseen forces (ASF MM 1, ins. 2, fols. 187v–188r; Buchanan 2021, 8–24). The entry is brief, which feels ironic given that the bean had traveled halfway across the world before it was copied into that Florentine manuscript.

The story of the St Ignatius bean begins in the Philippine archipelago. It is native to Samar, particularly in Catbalogan where it is called aguwason, dankkagi or igasud (in Cebuano). The plant later classified as Strychnos ignatii circulated in local medicinal practice long before it appeared in European books. Seventeenth-century Jesuit accounts describe it as a powerful seed that caused vomiting and purging. In humoral medicine, purging was an accepted way of removing illness from the body, so the bean’s effects made sense within European medical thinking (Pomet 1712, 27; Lewis 1761). Jesuit missionaries and pharmacists working in the Philippines recognized its strength and began sending both the seeds and written descriptions through missionary and commercial networks. As Buchanan explains, the bean entered European medicine through correspondence routes that linked Manila to Madras and London (Buchanan 2021, 8–24).

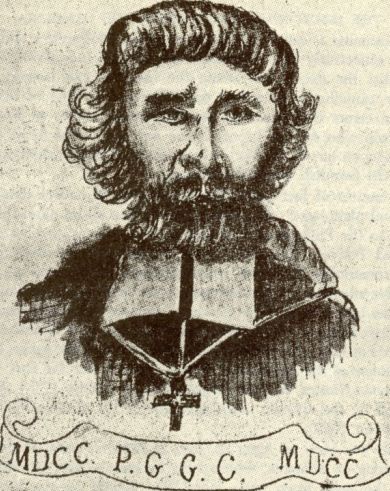

One key figure in this process was Georg Joseph Kamel (1661–1706), a Jesuit missionary, pharmacist, and naturalist based in Manila. Kamel wrote some of the earliest detailed accounts of Philippine plants and animals and introduced them to European scholars. He named the seed Faba Sancti Ignatii, after Ignatius of Loyola. In 1697–98 he sent specimens and drawings to Samuel Browne in Madras, who passed them on to John Ray in London. Ray included Kamel’s descriptions in the third volume of Historia Plantarum (1704), giving the bean a place in European botanical science (Ray 1704; Buchanan 2021, 8–24).

Once in print, the bean became easier to circulate. Engraved illustrations showed the pear-shaped fruit and its almond-like seeds. Images helped standardize the plant’s appearance and gave it scientific authority. As Harold Cook has argued, early modern commerce increased the value of knowledge based on physical objects, and botanical images helped authenticate those objects (Cook 2007). Writers such as Pierre Pomet described the bean as a strong purgative (Pomet 1712, 27), while William Lewis warned that it required careful preparation (Lewis 1761). The bean’s dramatic effects made it persuasive.

Its meaning shifted depending on where it appeared. In London it was discussed in scientific correspondence. In Paris it entered drug manuals and pharmacological trade. In Florence it became part of aristocratic recipe culture. In Anna Maria Luisa’s manuscript, the bean sits alongside coral, pearls, sulfur, sugar, and even rhino blood. It was one ingredient in a larger world of global remedies. At court, such materials signaled access to Jesuit networks, Portuguese trade routes, and imperial commerce. I thought it was amazing that s seed from the hinterlands of the Philippines could carry social meaning in Tuscany.

Modern chemistry tells us that the seeds of Strychnos ignatii contain strychnine and brucine, compounds that affect the nervous system and can cause convulsions if misused. Early modern physicians did not describe the bean in chemical terms, but they understood its danger and handled it cautiously (Lewis 1761). Its power as pharmakon—both medicinal and toxic—helped secure its reputation.

Scholars such as Pratik Chakrabarti have shown that eighteenth-century medicine was shaped by imperial materials drawn from colonial environments (Chakrabarti 2010, 3) while Kapil Raj argues that knowledge changes as it moves, gaining new meaning through circulation (Raj 2007). The St Ignatius bean is one example. A Philippine remedy was observed, renamed, classified in Latin, engraved, printed, and stored in European cabinets. Naming it after Ignatius of Loyola placed it within Jesuit intellectual territory. Latin taxonomy replaced local names. Its Philippine origins were acknowledged but reframed within European systems of knowledge.

By the eighteenth century, St Ignatius beans circulated alongside sugar from the Caribbean, roots from Africa, spices from Asia, and stones from Goa. Reading these details in Ashley Buchanan’s study of Anna Maria Luisa’s recipe book changed how I understood my short trip to Italy. It gave a deeper context to the Filipinos I had met in Florence and further illuminated Manila’s place in the early modern world. A single bean made that network visible. I began to wonder what else traveled with it from Manila to Florence along the routes that connected missionaries, merchants, printers, and princes.

References

Archivio di Stato di Firenze (ASF). MM 1, ins. 2, fols. 187v–188r. (cited in Buchanan 2018, 2013)

Buchanan, Ashley. “The Politics of Medicine at the Late Medici Court: The Recipe Collection of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667 – 1743).” (2018). USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

Buchanan, Ashley. “The Recipe Collection of the Last Medici Princess.” The Recipes Project, January 29, 2013. https://doi.org/10.58079/tcmd.

Chakrabarti, Pratik. Materials and Medicine: Trade, Conquest and Therapeutics in the Eighteenth Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

Cook, Harold J. Matters of Exchange: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Lewis, William. An Experimental History of the Materia Medica. London: J. Nourse, 1761.

Pomet, Pierre. A Complete History of Drugs. London: Printed for J. and J. Bonwicke, 1712.

Raj, Kapil. Relocating Modern Science: Circulation and the Construction of Knowledge in South Asia and Europe, 1650–1900. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Ray, John. Historia Plantarum. Vol. 3. London, 1704.