In his Kapilya installation for Art Fair Philippines, Max Balatbat assembles a makeshift chapel of salvaged wood and rusted rebar. This is supposed to represent the look of faith forged from marginal lives that the art writer Carla Gamalinda has compared to the one studied by Rey Ileto’s Pasyon at Revolution. A pendulum whip swings between sacks of rice and money, representing Catholic spirituality as narrowly lodged between devotion and desperation. Outside, a faceless child sampaguita vendor wearing a dress of stitched discarded textiles.These are arresting tableaux that function as symbolic illustration.

The materials are evocative and the motif and narrative clear and immediate. The work doesn’t demand that the viewer think into the contradictions; it tells you how to feel about them first, and quickly. Like how you would react to a viral prop engineered for views and likes. But it offers no structural tension to resist interpretation and no formal pressure that might force the viewer to wrestle with uncertainty.

This is exactly the trait I flagged 14 years ago in Balatbat’s paintings: work that signals weight by being literal rather than through ingenuity or irony. The earlier pieces evoked nostalgia and confident familiarity with the tagpi-tagpi, the informal settlement house, which is the main form of Kapilya. The materiality on display may be raw but the meaning is manufactured for ready legibility.

Here’s where the larger problem shows up. Manila’s art writing redistributes this work like a propaganda machine, repeating the artist’s lived story and stated intentions without interrogating the visual grammar that produces those meanings. Most reviews describe biography and context but avoid formal critique. So I looked up nearly every art writer I know, and the silence was telling. Everyone seems to be in on it, or at least unwilling to break ranks.

The choice of venue is too tempting to ignore. Circuit Makati, touted as an arts and lifestyle hub, sits on the former grounds of Hippodromo, or the horse racing track. One cannot overstate the parallelism of speculation and the spectacle between the art fair and an imperial pastime.

Like much of the fair itself, the metaphors are so on the nose it borders on fiction. One friend described the site of the art fair as six concentric circuits of hell, Danteesque (minus 3 layers) in layout and mood.

The mantra of Robert Hughes, “nothing If not critical”, comes to mind. Seriousness in art is not sincerity or intention but pressure—on form, on perception, on the viewer. Hughes had little patience for work that uses piety, politics, or biography that does not translate into provocation. And worse, only serves as insulation from critique. By that measure, Kapilya suffers from an unwillingness to disrupt rather than simply affirm its own narrative frame.

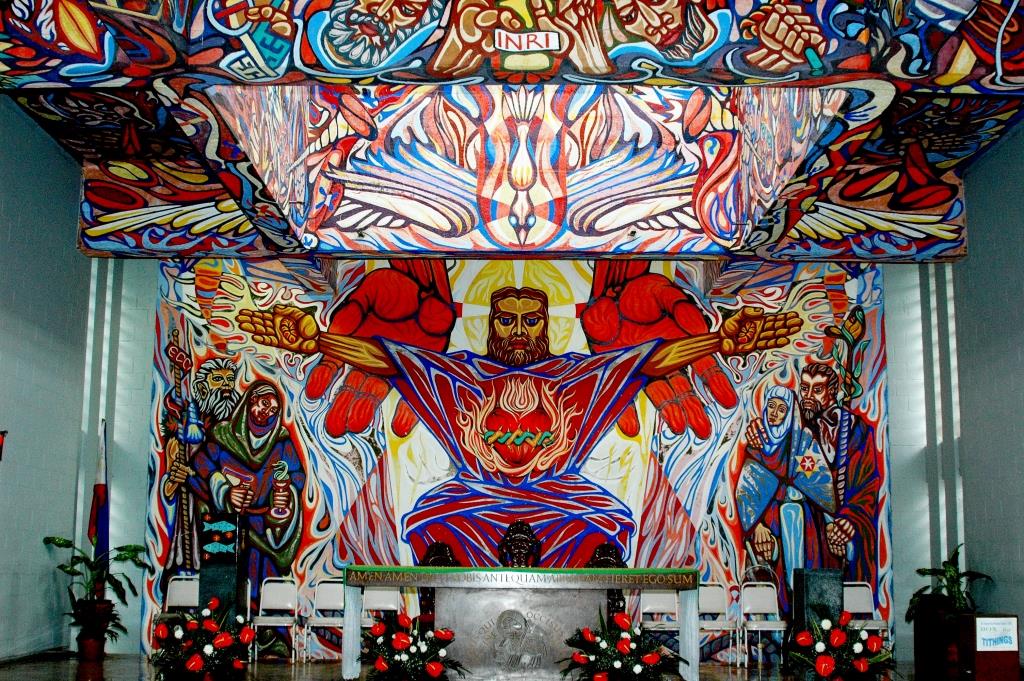

Or at the very least, from a thin engagement with art history. Which is what compelled me to come out of the woodwork and write. The crucified Christ figure inevitably recalls Alfonso Ossorio’s The Angry Christ, painted in Victorias, his family’s hacienda chapel dedicated to the St. Joseph the Worker, where apocalyptic excess carried genuine formal and spiritual risk. Here, however, Christ is emptied of that tension. He becomes a stand-in for the Manila art scene itself: a self-flagellating ritual of self-affirmation, where suffering is rehearsed and criticism is treated as an unwelcome guest.