The following notes draw from the wealth of information shared by scholars, collectors, archival researchers, and art history networks following the loan of Juan Luna’s (1857-1899) La Bulaqueña (1895) to the Louvre Abu Dhabi (June 2025-June 2026). It brings together insights from literature, oral histories, institutional records, and recent findings that have come to light in the wake of the painting’s international exhibition. All authors and sources are duly cited in the endnotes. This is a developing feature, please feel free to contact the author for any corrections and additional insights.

***

Juan Luna’s La Bulaqueña, painted in 1895, is one of the few surviving portraits by the artist that depicts a Filipina subject in native attire. Created on the eve of the Philippine Revolution, the painting shows a young woman from Bulacan wearing the traje de mestiza—a formal dress made of piña fiber that became a national symbol of grace and cultural identity.(1)

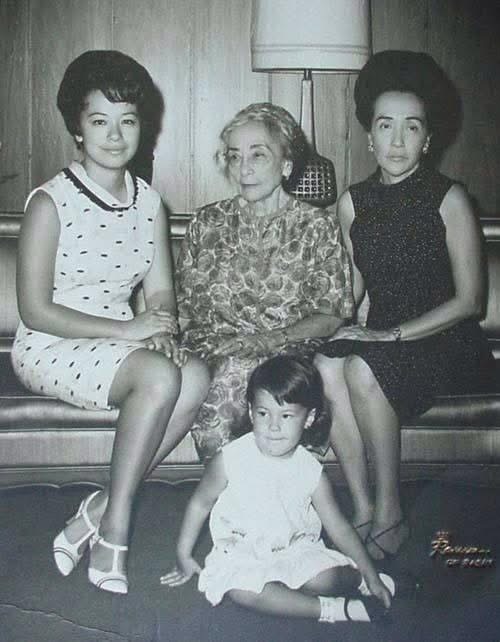

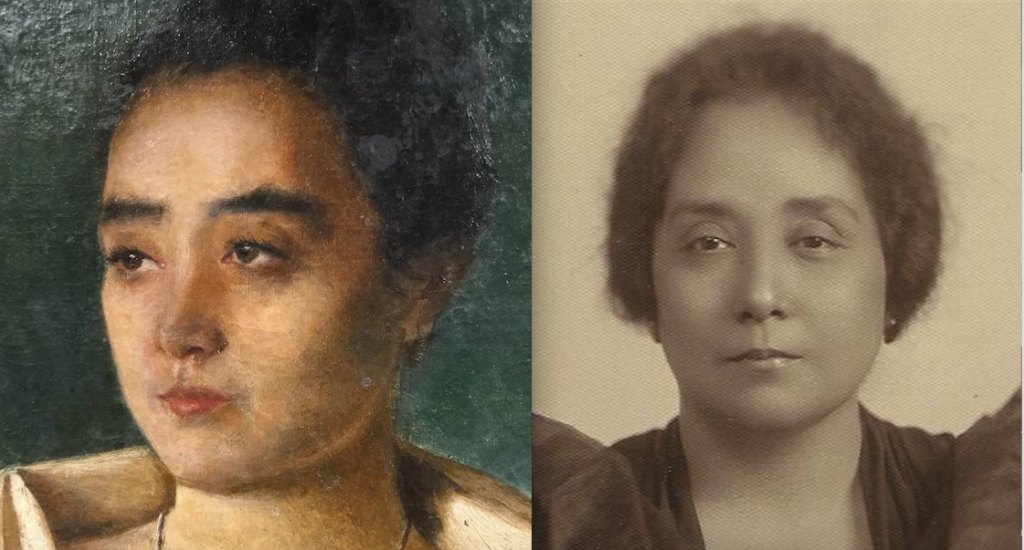

The sitter has been confirmed as Emiliana Yriarte de Santos (née Trinidad; January 14, 1878–March 22, 1971) (fig. 1). Santiago Albano Pilar et al. identified her as early as 1994; Ramon Villegas reaffirmed this in Arts of Asia (2004); and Ambeth Ocampo’s photographic evidence in 2014 definitively established her as La Bulaqueña. (2) She was around 17 years old when she posed for Luna. The painting was at times titled Una Bulaqueña (“A Woman from Bulacan”), which following conventions of Spanish conjugation, means that the sitter is unknown. But even this title affirms its setting and subject as distinctly local; “Bulaqueña” from Bulacan, which comes from the Tagalog word bulak, meaning cotton, referencing the abundance of cotton plants that once grew in the area. (3) This etymology reflects the province’s early agricultural identity and hints at the material subject of the portrait. The portrait was likely completed in Luna’s Manila studio and reflects his shift from large historical canvases to relatively smaller, more intimate portraits of Filipinos.(4)

This moment marks the crystallization of the María Clara ensemble—camisa, pañuelo, saya, and tapis—setting the stage for a closer visual reading of how fashion articulates class and femininity. The sitter stands at ease, lifting her skirt slightly to reveal the tapis beneath, hands folded over a cotton handkerchief on her left hand. (5) A folded fan is suspended from her right hand.

According to this fascinating discussion on the language of fans by Alexandra Starp, this means “you are too willing”. In historian Ambeth Ocampo’s discussion of prewar fan language, however, this gesture signifies “I already have a boyfriend” or indicates unavailability.(6) In early modern portraiture, the handkerchief functioned as both an ornamental and symbolic object—signaling cleanliness, modesty, or flirtation depending on context. In La Bulaqueña, its inclusion recalls similar depictions in European portraiture, such as the Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo, 1562 (fig.2a), where the handkerchief emphasizes elite femininity and domestic virtue. At the same time, in Cesare Vecellio’s costume books (fig. 2b), courtesans also hold handkerchiefs, suggesting erotic availability. This visual tension is echoed in La Bulaqueña, where the woman’s demure pose and elegant dress coexist with subtle gestures, like the exposed handkerchief, that complicate the reading of her virtue. As NYU professor Bella Mirabella observes, such accessories were “small, but powerful” objects through which women navigated the contradictory demands of decorum and desire.(7)

These coded layers of meaning to the portrait suggests that the woman is not a passive subject but one who exercises covert agency. Within the context of late nineteenth-century Filipino society, her pose may be read as an assertion of autonomy embedded within the conventions of colonial portraiture. The fabric is rendered with fine detail, showing Luna’s Manila and European academic training which involved imitating from prints and replicas of masterworks. (8) Luna later studied at the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid and lived in Paris, where he encountered the works of Velázquez, Gérôme, and Bouguereau, among others.

The traje de mestiza worn in the painting was a mix of colonial Spanish styles and indigenous Philippine textiles. By the 1890s, it was already considered a statement of Filipino identity, especially among elite women.(9) This fashion would later influence national style icons such as couturier Pitoy Moreno and former First Lady Imelda Marcos, who used the mestiza gown as a symbol of Filipina elegance and nationhood.(10)

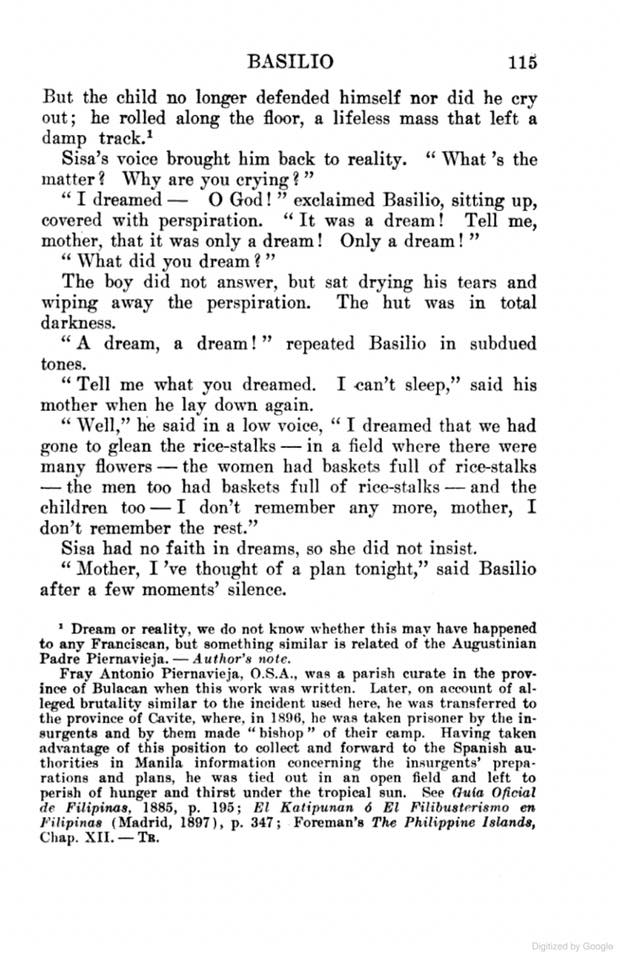

The Maria Clara is named after the mestiza heroine of José Rizal’s 1890 novel Noli Me Tangere and became a popular formal dress among elite Filipino women at the turn of the twentieth century. It remains the only national costume named after a literary character. Juan Luna, who made bocetos to illustrate the 1891 edition of Noli, further entwines the painting La Bulaqueña with Rizal’s world. That connection deepens when we consider that Emiliana’s father, the Augustinian friar Antonio Piernavieja, is widely believed to have inspired the character of Padre Salvi ( infra for biographical details). In a footnote to Chapter 17 (“Basilio”) (fig.5) of Noli Me Tangere, Rizal pointedly mentions Piernavieja including the allegations of murder and fathering an illegitimate child. Archival evidence indicates Piernaveja had three children, one of whom appears in correspondence between Juan Nakpil and Andrés Bonifacio.(11) This biographical thread situates La Bulaqueña not only within the sphere of colonial portraiture and domestic ideology, but also within the charged literary and political milieu that Rizal inhabited and sought to expose.

By the late nineteenth century, the Maria Clara gown had become an iconic signifier of mestiza beauty and virtue, shaping ilustrado ideals of desire. The gown consists of four main parts: the camisa (a collarless, bell-sleeved blouse), the saya (a floor-length skirt), the pañuelo (a shawl draped over the shoulders), and the tapis (a short overskirt). It developed from the traditional baro’t saya worn by early Filipino women.(12)

The pañuelo was added to provide modesty over the sheer camisa, which was often made of piña or jusi. The tapis was worn to prevent the transparency of the skirt. It was usually made of opaque fabrics like muslin or madras.(9) While Bulacan had its own cotton textile industry, muslin, a fine cotton fabric from India and Bangladesh, likely arrived in the Philippines via South and Southeast Asian trade routes. Muslim and Arab merchants introduced it as early as the 14th century, with Portuguese trade expanding its circulation by the 16th. Imported muslin introduced cotton as a valued fabric in the islands.

Variants of the saya included the dos panos (two-panel skirt) and siete cuchillos (seven-gore skirt). The camisa sleeves were shaped like bells or angel wings. The pañuelo was often elaborately decorated, while the tapis was usually plain. The ensemble was labor-intensive to wear and reflected both native sensibility and colonial influence. (13)

Like the stereoview of Spanish mestiza women (fig. 3), taken a few years after La Bulaqueña, images of the traje de mestiza worn by elegant, fair-complexioned women reveal the symbolic power of costume to express both class and identity. Like the painting, the photograph blends local textile tradition with colonial-era ideals of femininity and domesticity.

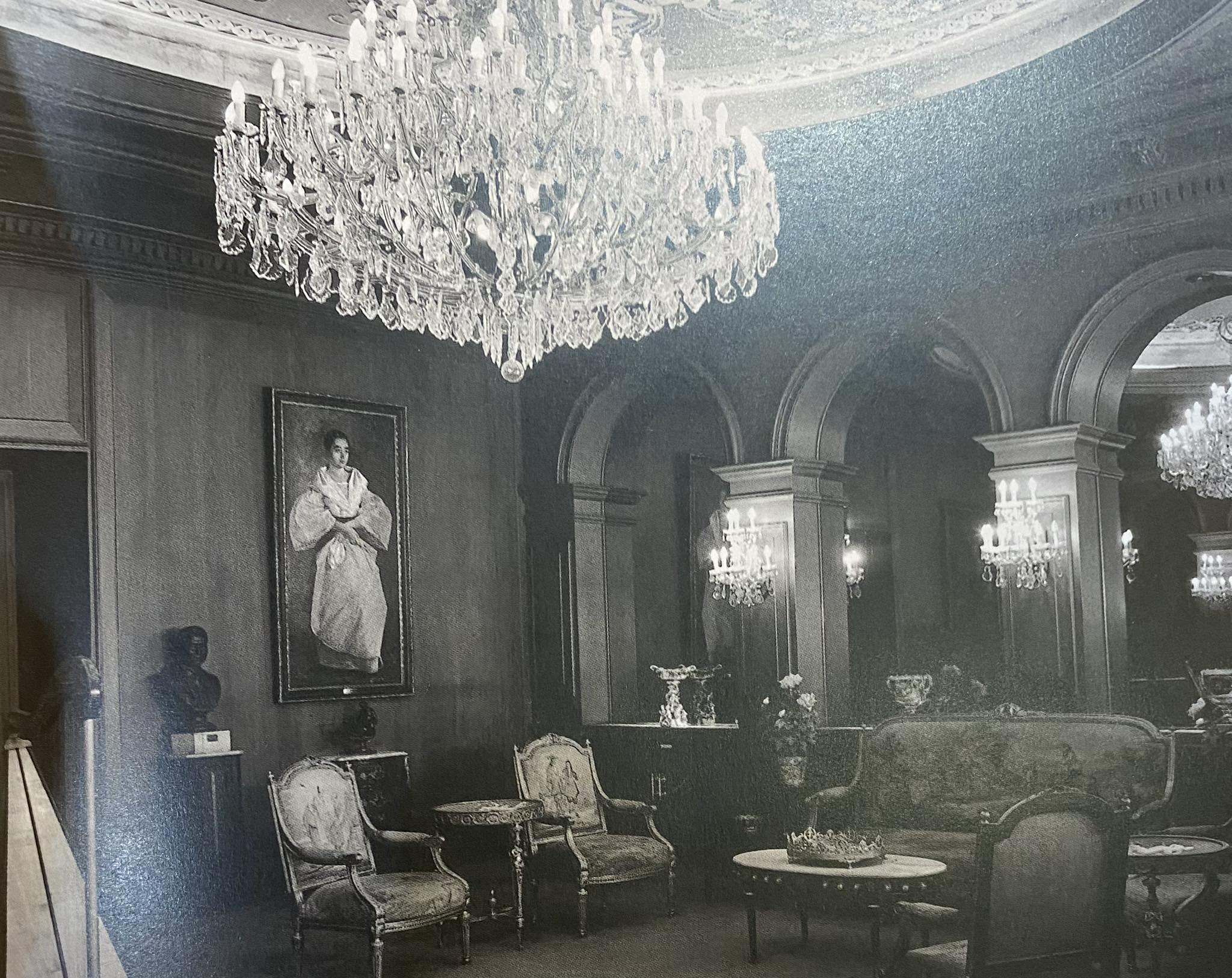

To safeguard La Bulaqueña during the Second World War, Emiliana sold the painting for ₱200 in Japanese military currency—likely to Jorge Vargas, who facilitated its transfer to Malacañang Palace. Because the National Museum’s infrastructure had not yet been reconstructed, the painting was displayed at the Palace, most notably in the Music Room during the Marcos era. (14) Although Emiliana’s family attempted to recover the work during that time, their efforts were unsuccessful. In 1996, the painting was formally transferred to the National Museum of Fine Arts, where it was opened for public viewing since at least 2008 when it was declared a National Cultural Treasure. Emiliana Yriarte-Trinidad passed away on March 22, 1971, at the age of 93, and was buried at Sanctuario de San Antonio in Makati.(15) At the Louvre Abu Dhabi, La Bulaqueña hangs between Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s The Cup of Chocolate (fig. 4) and Édouard Manet’s The Bohemian. (16)

Despite its long-known authorship and confirmed model, public debate continues to fixate on the sitter’s identity. Claims about a romantic relationship between Luna and Emiliana Yriarte (her maiden name) persist, though no historical evidence supports these speculations.

Let’s quickly run through the biographical details of the sitter.

Emiliana Yriarte Trinidad was born on January 14, 1878, in Caingin, San Rafael, Bulacan, to Bonifacia Yriarte-Trinidad and Antonio Piernavieja, a Spanish Augustinian friar from Valladolid who served as parish priest of San Rafael between 1868–1873 and 1875–1877. During his tenure, Piernavieja oversaw the construction of the town convent and a bridge linking San Rafael to Baliwag. (17) Piernavieja was killed by Filipino revolutionaries in Maragondon, Cavite, in 1897 for collaborating with Spanish colonial authorities (fig. 6).

Raised in a wealthy household, Emiliana was taught to be religious by her father. She studied painting and drawing under Juan Luna, who is believed to have served as her private tutor. Around 1895, she posed for Luna’s Una Bulaqueña. Although some accounts speculate that Luna pursued a romantic relationship with her—giving her artworks and sketches—Emiliana’s family reportedly disapproved due to their age difference and Luna’s controversial reputation following the deaths of his wife and mother-in-law. Emiliana clarified later in life that she was not the woman in Tampuhan (1895) (fig. 5), a painting depicting a lover’s quarrel completed in the same year as La Bulaqueña. (18)

Luna may have introduced Emiliana to his friend, Dr. Isidoro de Santos, a fellow Filipino patriot and one of the doctors who attempted to revive Luna after his fatal heart attack in 1899. Emiliana and Isidoro eventually formed a domestic partnership (Isidoro had two other partners) and had five children together, although Emiliana remained financially independent. Their youngest daughter, Edita de Santos-Orosa, inherited many of Luna’s works, including Tampuhan. (19)

There is a sizable body of scholarship underscoring the enduring interest in and cultural importance of this painting within the Philippines, ranging from broad surveys of national art history to focused monographs on Luna’s work and its reception among Filipino audiences. (20)

A recent notable discussion of La Bulaqueña appears in Kathleen Cruz Guittierez’s Unmaking Botany, where she juxtaposes Felix Martínez’s 1893 illustration ¡Sampaguita!—with its barefoot vendor framed by bamboo and palm, offering garlands of jasmine—with Luna’s 1895 portrait of the mestiza elite. Cruz Guittierez argues that although Martínez’s vendor is anchored to her rural identity by the simplicity of her baro’t saya and the diaphanous glow of youth—underscored by the near-imperceptible fingers of her left hand merging with the jasmine garland—both images nonetheless radiate a quiet sensuality. In Martínez’s ¡Sampaguita!, the blurred boundary between finger and flower prompts viewers to ask whether the garland, the vendor, or both are eponymous; in Luna’s portrait, the invocation of the cotton fiber—both the namesake of her birthplace and the very material of her attire—similarly veils desire beneath an air of modesty and refinement. (21)

In popular culture, La Bulaqueña inspired Orange & Lemons’ 2024 official music video of the same name—starring beauty queen Chelsea Manalo and directed by Everywhere We Shoot.(22) It was likewise commemorated by the Philippine Postal Corporation in its 1994 “Stamps on National Symbols” series, where the 7-peso issue portrayed the Baro’t Saya (traje de mestiza) emblematic of national costume.(23)

Photo: La Bulaqueña – Orange & Lemons (Official Music Video), 2024.

La Bulaqueña was painted during a moment of national awakening. Filipino intellectuals like Luna, Rizal, and their peers in the Ilustrado class were trying to imagine what a Filipino nation could look like. In this painting, Luna gave it a mestiza face. The painting’s quiet dignity stands in contrast to Luna’s more dramatic historical canvases, but it carries no less weight.

Another point of discussion which we might save for another explainer would be the fragility of our visual heritage. Many masterpieces were destroyed or looted during the Second World War. That La Bulaqueña survived is already remarkable. That it continues to spark conversation whether in art history or popular culture over a century later speaks to its power. It is in this light, that discussions should move beyond tittilating gossip or its elite provenance, but on the dress, the woman, and what both represented for the generation that sought independence through cultural uplift.

It is remarkable to think that the former Parisian Juan Luna now has a work in the Louvre Abu Dhabi—a French institution planted in the Gulf—linking French salons where Luna and Rizal once dreamed of nationhood to Dubai’s expatriate crowds who’ll pay to glimpse what once hung freely in Manila. As the “Pearl of the Orient,” our portrait sails across seas that shaped our art and diaspora. As it travels abroad and is viewed by new audiences, Filipinos are reminded of the painting’s layered legacy. Calling it Luna’s “Mona Lisa” may flatter and make great headlines, but it also risks diminishing the work’s historical and political gravity.(24). The Louvre Abu Dhabi does it justice by calling it the “National Treasure’s Journey: From the Pearl of the Orient to the Emirates.”

The loan to the Louvre has been widely praised for vividly reaffirming our century-old ties to the Middle East. As someone who’s hurried past it on countless museum tours, I can’t help but wonder: what might a full, devoted art-historical study of this “Pearl of the Orient” reveal about our identity and the local, European, and Gulf networks that shaped its destiny?

Endnotes

- Cultural Center of the Philippines, Encyclopedia of Philippine Art, “La Bulaqueña” entry, 2020.

- Noel Valdellon, N. Ferrer, and Santiago A. Pilar, “La Bulaqueña,” Encyclopedia of Philippine Art, Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1994.; Ramon Villegas, “Juan Luna: Filipino Painter and Patriot”, Arts of Asia (Hong Kong: Arts of Asia Publications, 2004); Ambeth Ocampo, “Juan Luna’s ‘La Bulaqueña’ finally identified,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 28, 2017.;

- Nick J. Lizaso, “Bulakan with a K,” Manila Bulletin, January 13, 2021.

- Pilar, Santiago Albano. Juan Luna, the Filipino as Painter. Philippines: Eugenio López Foundation, 1980, 113.

- Alexandra Starp. “The Secret Language of Fans.” Objects of Vertu, April 24, 2018. Sotheby’s. .; Ambeth Ocampo, “Fan Language,” Looking Back, Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 2, 2005, 13.

- CCP Encyclopedia, 2020; Nakpil, Lisa Guerrero. “Juan Luna’s ‘Mona Lisa’ goes to Louvre Abu Dhabi,” The Philippine Star, June 15, 2025.

- Bella Mirabella, “The Contradictory Life of the Handkerchief,” Martine van Elk (blog), September 18, 2016, https://martinevanelk.wordpress.com/2016/09/18/the-contradictory-life-of-the-handkerchief/.; Göttler, Christine, Lucas Burkart, Susanna Burghartz, and Ulinka Rublack. Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450–1750: Objects, Affects, Effects. Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

- Eugenio Matibag, “A Filipino Painter in Paris: Juan Luna in the Field of Cultural Production”, Perspectives in the Arts and Humanities Asia 7, no. 2 (2017): Article 3.

- Gino Gonzales and Mark Lewis Higgins, Fashionable Filipinas: An Evolution of the Philippine National Dress in Photographs 1860–1890 (Mandaluyong: Bench and the Cultural Center of the Philippines, 2015); Salvador Bernal and Georgina Encanto, Patterns for the Filipino Dress: From the Traje de Mestiza to the Terno (Quezon City: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 2001); Sandra Castro, Fashionable Fabrics: The Mestiza Dress from the Nineteenth Century to the 1940s; Philippine Folklife Museum Foundation, “Traje de Mestiza,” accessed January 26, 2019; Arlo Custodio, “Championing Maria Clara beyond the Walls of Intramuros,” The Manila Times, May 27, 2018.

- Ambeth Ocampo, “Who Was Juan Luna’s La Bulaquena?,” National Commission for Culture and the Arts, December 27, 2004, http://www.ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/articles-on-c-n- a/article.php?i=282&subcat=13; Pitoy Moreno, Philippine Costume (Manila: J. Moreno Foundation), 1995, 44-47, 139-142.; Mina Roces, Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2010), 24.

- Floro Quibuyen. “Rizal and Filipino Nationalism: Critical Issues.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 50, no. 2 (2012): 145–181.

- Moreno, Philippine Costume, 191. 44-47, 139-142; See, Pitoy Moreno, “Maria Clara, Philippine Costume,” Koleksyon: Filipino Heritage, August 19, 2009, archived at Internet Archive, accessed June 16, 2025. See also

- Noel Valdellon, N. Ferrer, and Santiago A. Pilar, “La Bulaqueña,” CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Digital Edition, November 18, 2020.

- Isidra Reyes, Facebook post, “Jeremy Barns, Director of the National Museum, confirms that the transfer of La Bulaqueña to the museum was authorized by President Fidel V. Ramos,” April 11, 2023. Accessed June 15, 2025.

- Ambeth Ocampo, “Juan Luna’s ‘La Bulaqueña’ Finally Identified,” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Lifestyle section), May 28, 2017.; See also Lisa Guerrero Nakpil, “Juan Luna’s ‘Mona Lisa’ Goes to Louvre Abu Dhabi,” Philippine Star, June 15, 2025.

- Ramon N. Villegas, “Juan Luna: Filipino Painter and Patriot,” Arts of Asia 34, no. 6 (June 2004): 66–83; Cruz, E. Aguilar. Painterly Affections, 1976; Nakpil, 2025; Bordey, 2024.

- Pedro Galende, Angels in Stone: Architecture of Augustinian Churches in the Philippines, Manila: San Agustin Museum, 1996., 117-167.

- Rosalinda L. Orosa, “Luna’s Original Model for Tampuhan and Bulakeña / An Update on Walled City,” Philippine Star, April 30, 2011.

- Karl de Santos, Facebook post, Save Ides O’Racca, March 13, 2021; Karl de Santos is a descendant of Emiliana Yriarte de Santos.

- Ambeth R. Ocampo, Looking Back (Manila: Anvil Publishing, Incorporated, 2012); Between Worlds: Raden Saleh and Juan Luna (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 192, 196; Santiago Albano Pilar, Juan Luna, the Filipino as Painter (Manila: Eugenio López Foundation, 1980), 203, 206; Emmanuel Torres, “Juan Luna: A Feast for Heroes,” Archipelago (Manila: Bureau of National and Foreign Information, Department of Public Information, 1974).; Laya, Jaime C.. Letras Y Figuras: Business in Culture, Culture in Business. Indonesia: Anvil Pub., 2001.

- Kathleen Cruz Guittierez, Unmaking Botany (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024), 112–15.; See, Stéphanie Marie R. Coo, Clothing and the Colonial Culture of Appearances in Nineteenth-Century Spanish Philippines (1820–1896) (PhD diss., Université Nice Sophia Antipolis, 2014).

- GMA Integrated News, “Chelsea Manalo stars in Orange & Lemons music video for ‘La Bulaqueña’,” GMA News Online, September 20, 2024 gmanetwork.com.

- stampdigest, “Stamps on National Symbols – Philippines 1993–96,” StampDigest, May 21, 2019

- Lisa Guerrero Nakpil, “Juan Luna’s ‘Mona Lisa’”, 2025.