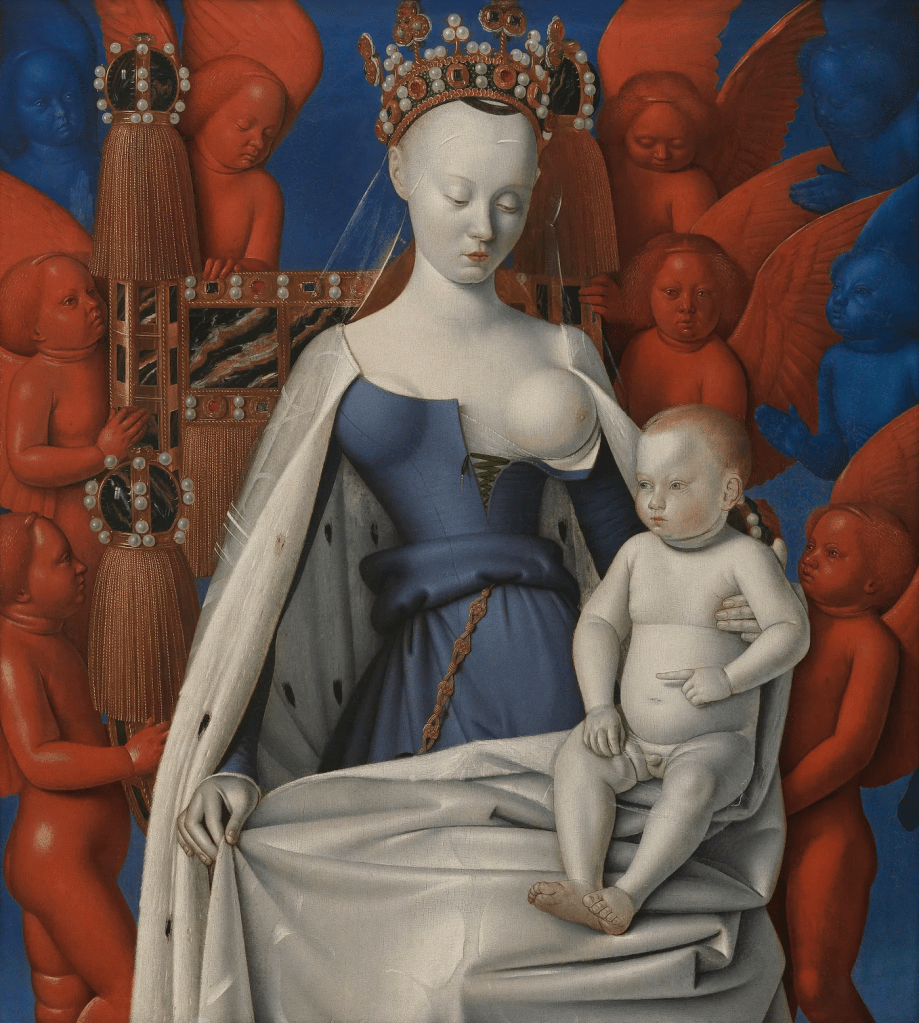

Painted ca. 1452–58 as the right wing of the Melun Diptych, Madonna and Child Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim by Jean Fouquet constitutes a singular contribution to the visual culture of the French court. Executed in oil on panel, the painting presents a Marian figure suspended between celestial abstraction and courtly specificity. Seated on a throne adorned with precious stone inlay and flanked by red and blue seraphim, the Virgin emerges in an ambiguous visual register—at once ethereal icon and elite portrait. Scholars have frequently addressed the Virgin’s idealised physiognomy, her unnaturally pale, marble-like skin, and the anatomically stylised form.¹ Yet less attention has been paid to the role of ornament, particularly pearls, which appear not only as material embellishment but as theological and aesthetic agents, interfacing with contemporary court fashion, devotional ideology, and ceramic culture.

The profusion of pearls across the Virgin’s crown, bodice, and neckline announces a visual rhetoric of accumulation associated with sacred royalty. Their careful arrangement—clustered with gemstones and framed by gold filigree—recalls the regalia of late Gothic monstrances and ecclesiastical crowns.² However, their dense and decorative presence also resonates with the aesthetics of fifteenth-century Italian maiolica, especially istoriato wares from Deruta and Faenza. In these ceramic traditions, artists employed white tin-glazed droplets and gold luster to simulate pearls and other jewels, embedding them into the narrative and ornamental schema of the object.³ These pseudo-gems offered a surface language of preciousness, transforming utilitarian ceramics into visual analogues of goldsmith work. As Dora Thornton has shown, such ceramics were integrated into systems of gift exchange and elite display, their surfaces coded with the values of wealth and refinement.⁴ Fouquet’s pearls function within a parallel register: they are not isolated embellishments but part of a material and optical strategy to produce sanctity through ornament.

This intersection of sacred image and courtly taste is further accentuated by the glazed effect of the painting itself. The high saturation of blues and reds, paired with the polished reflectivity of the flesh and fabric, suggest a painter attuned to the visual idioms of ceramic and enamel work. Fouquet’s travels to Italy in the 1440s likely brought him into contact with both Tuscan panel painting and decorative ceramics in urban centers such as Siena and Rome.⁵ The influence of these encounters is legible in the jewel-like palette of the Melun Madonna, where colour and surface perform a theological function. The deep lapis blue of the angels and the satin sheen of Mary’s gown do not merely decorate; they refract and distribute light, staging the body of the Virgin as a liturgical object—part reliquary, part vision.

This surface strategy reaches its apex in the depiction of Mary’s exposed breast, a detail that has long perplexed viewers. Highly stylised and improbably spherical, the breast projects from the heavy garment with neither weight nor softness. Instead, it gleams with a hardness and uniformity that invites comparison to a pearl—a parallel reinforced by its placement amid other ornaments and its theological resonance. In Marian devotion, the breast signified nourishment and maternal intercession; in this image, it also reads as a precious object, a jewel of miraculous generation.⁶ The breast as pearl fuses body and adornment, confounding distinctions between flesh and relic, matter and metaphor. Its stylisation exemplifies a broader visual economy in which Marian purity is rendered as mineral perfection.

Further contributing to the spectral quality of the figure is the pale tonality of her flesh, which recent technical studies suggest was intensified over time by the fading of red lake pigments.⁷ These organic pigments, prized for their translucency, are notoriously unstable and vulnerable to light. Their degradation has led to the loss of warmth and chromatic variation in the skin tones, producing a bleached and near-monochromatic effect. This paleness, while likely unintentional in degree, aligns with contemporary ideals of noble femininity.⁸ As noted in court portraits of Agnès Sorel—long believed to be the model for Fouquet’s Virgin—aristocratic beauty standards privileged whiteness as a mark of moral and genealogical purity. Lead-based cosmetics, combined with vinegar and other bleaching agents, were employed to produce this effect artificially.⁹ The Melun Madonna thus emerges as a site where theological virtue and courtly fashion converge.

The physiognomic resemblance between Fouquet’s Virgin and Agnès Sorel, mistress of Charles VII, has been a point of sustained scholarly interest. Sorel was a prominent presence at court, known not only for her beauty but for her strategic deployment of appearance in cultivating royal favour and moral authority.¹⁰ Portraits of Sorel often depict her with exposed breasts and lavish jewelry, particularly strands of pearls—a sartorial language that encoded both dynastic fertility and elevated virtue.¹¹ By transposing Sorel’s features onto the body of the Virgin, Fouquet does not merely insert a likeness; he collapses the typologies of queen, saint, and mistress, constructing a composite figure whose sanctity is refracted through the aesthetics of courtly privilege.

The identity of the commissioning patron, Étienne Chevalier—treasurer to Charles VII and executor of Sorel’s estate—further complicates this image. The Melun Diptych was likely commissioned shortly after the death of Chevalier’s wife, Catherine Budé, and originally installed over her tomb in Notre-Dame of Melun. Yet the Virgin’s features bear no resemblance to Budé and have been widely identified instead with Sorel, who died two years earlier under contested circumstances.¹² If the Virgin is read as a disguised portrait of Sorel, then the painting becomes a political and affective offering—honouring not Chevalier’s wife, but the memory of the king’s mistress and the courtly milieu that defined her.

In this context, pearls serve as mediating devices, connoting both sacramental value and erotic prestige. Their dual role—adorning both relics and women—allowed them to circulate across sacred and secular spheres with equal potency. In devotional texts, the pearl stood for the Word made flesh, concealed within the oyster of Mary’s womb.¹³ In courtly settings, it adorned the bodies of those closest to power. Fouquet’s visual logic absorbs both traditions, rendering the Virgin’s body as a site of jewel-like reverence. Her sanctity is not rendered through ascetic withdrawal, but through the accumulation of luxury—a visual theology rooted in the display of matter.

The Melun Madonna thus participates in a broader cultural economy in which sanctity, beauty, and value are not opposed but mutually constitutive. The painting’s surface operates as a semiotic field, where pigments, pearls, and glaze-like effects generate meaning not through symbolic restraint but through sensorial excess. Far from retreating into spiritual abstraction, Fouquet’s Virgin embraces the material languages of wealth, ornament, and elite visuality. She emerges not simply as the Queen of Heaven, but as the court’s own idealised projection of virtue—a body made luminous by the very surfaces that surround it.

Notes

- Penny Howell Jolly, Madeleine’s Mirror: Women, Angels, and the Image of the Virgin Mary in Jean Fouquet’s Melun Diptych, Gesta 32, no. 2 (1993): 108–17.

- Margaret Scott, Late Gothic Europe, 1400–1500 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1980), 54–55.

- Timothy Wilson, Maiolica: Italian Renaissance Ceramics in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2003), 28–29.

- Dora Thornton, The Scholar in His Study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 101–106.

- Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 86–91.

- Marina Warner, Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary (New York: Vintage, 1983), 231–36.

- Jo Kirby, The Technical Examination of Jean Fouquet’s Melun Diptych, in National Gallery Technical Bulletin 28 (2007): 14–22.

- Evelyn Welch, Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 147–48.

- Susan Groag Bell, “Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture,” Signs 7, no. 4 (1982): 742–68.

- Kathleen Wellman, Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 55–65.

- Rosalind Brown-Grant, Agnès Sorel and the Construction of Courtly Female Virtue, French History 21, no. 1 (2007): 1–17.

- Véronique Chatenet, Jean Fouquet et le portrait à la cour de Charles VII, Revue de l’art, no. 123 (1999): 9–20.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe (New York: Zone Books, 2011), 91–95.

Email the author for the full article