Nicola Kanmany John’s dissertation has critically examined the narrative surrounding the Filipino artist Victorio Edades’s Armory Show conversion to Modern Art. Edades is often regarded as the “father of Philippine modernism” and Kanmany John’s findings challenges the claim that a Seattle exhibition inspired by the 1913 Armory Show of New York fundamentally shifted Edades’ artistic approach, leading him to abandon traditional art in favor of modern art. This account, popularized in two key biographies—Edades: National Artist (1979) and Edades: Kites and Visions (1980)—is scrutinized in light of historical inconsistencies, alternative evidence, and visual analysis of Edades’ early works.

The biographies emphasize that Edades encountered modernist works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso during his time in Seattle in the early 1920s. The biographies portray this event as a defining moment in his rejection of the conservative art traditions he had previously embraced. However, no records substantiate the occurrence of a significant Armory Hall-inspired exhibition in Seattle during this period, apart from a smaller 1925 display of modern art reproductions at the University of Washington, where Edades studied.

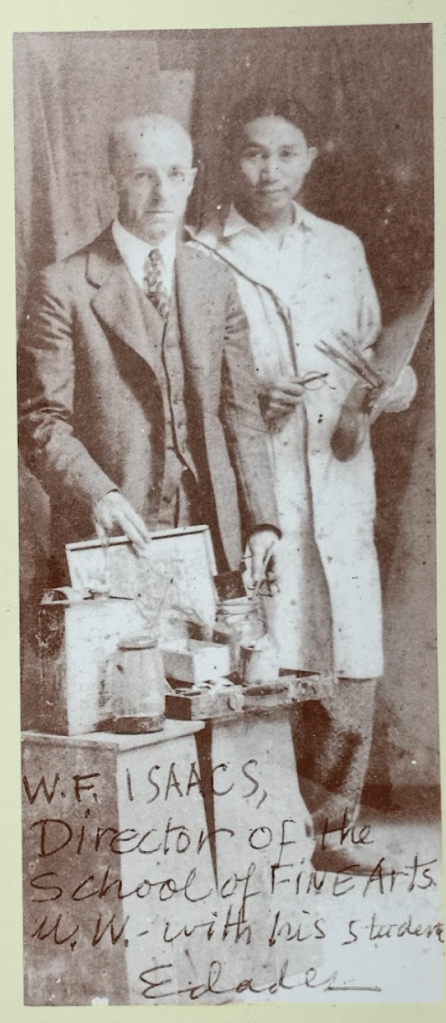

Rather than a sudden conversion to modernism sparked by this mythical exhibition, Kanmany John argues that Edades’ early modernist tendencies were likely shaped by his instructors, Walter Isaacs and Ambrose Patterson, who themselves engaged with modernist ideas and techniques. Both professors’ works show post-impressionist influences, undermining the narrative that Edades rebelled against a conservative academic environment. Furthermore, analysis of Edades’ student works suggests a gradual exploration of modernist aesthetics, blending influences from his mentors, the Ashcan School, and Mexican muralists like Rivera. The influence of Mexican murals has not been fully argued in the dissertation but there is enough evidence to assert this through Edades’s writings on WPA projects, a connection that Kanmany John has unfortunately overlooked.

Kanmany John’s investigation also highlights that Edades’ early works, while diverging from Philippine pastoral traditions, do not exhibit a clear stylistic break attributable to Cézanne or Gauguin. Instead, his art reflects a synthesis of American and French modernist elements, informed by his personal experiences as a foreign student in Seattle. Contrary to the biographies’ portrayal of a combative relationship with his Seattle peers and teachers, evidence suggests a collegial and supportive environment that celebrated his achievements.

Her study critiques the Armory Hall narrative as a retrospective construction that simplifies the complexity of Edades’ artistic development. This disseration proposes a more nuanced view, situating Edades’ modernism as a product of his interactions with both local and international artistic currents during his formative years in Seattle. It would be exciting to see this dissertation turned into a book project soon as Filipino art historians have been struggling to fill the narrative of Manila’s rapidly evolving art scene.