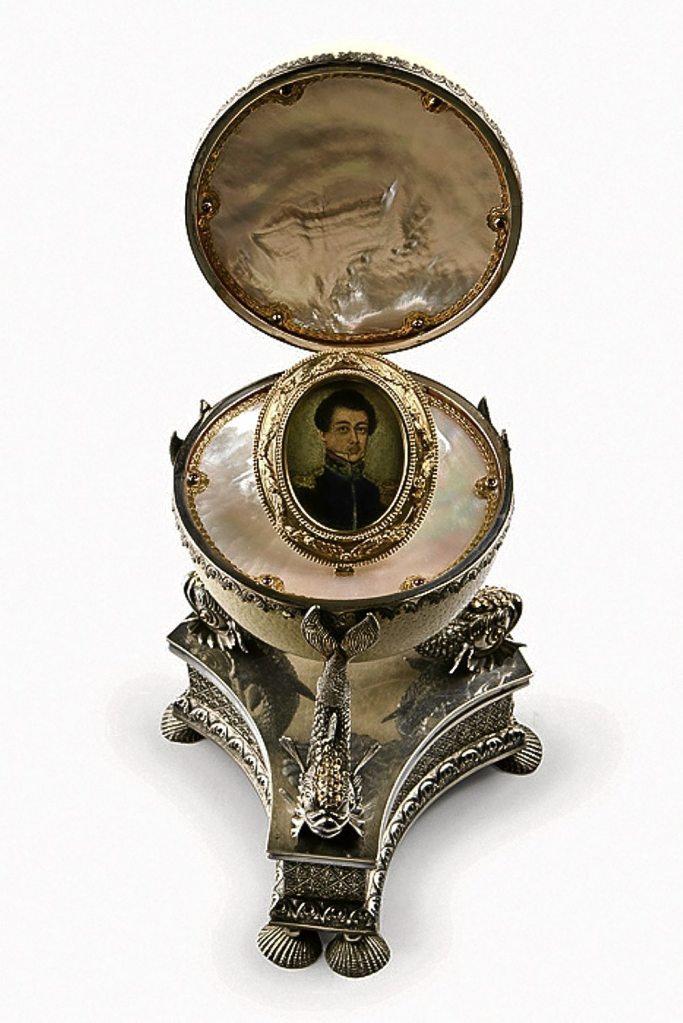

Fig. 1 Damian Domingo, self-portrait, gouache on oval-shaped ivory sheet, 6.1 cm x 4.8 cm, 1826. Source: Ayala Museum.

What is known of Domingo’s physical appearance comes from a miniature painted on an ivory sheet in 1826, which is also the oldest known self-portrait made in the Philippines. All catalogs and previous scholarship on the ivory portrait list the paint medium as oil but from my inspection of the object at the Ayala Museum and from comparing it with techniques of hatching in conventional paintings on ivory, I concluded that Domingo painted it in watercolor, which is the same paint medium as the Tipos del Pais. His other portraits on ivory were also done in watercolor. This note on materiality is crucial as it further connects Domingo’s practice of painting to the miniature as an artistic form, which also developed in trading ports across the globe, particularly in New England (Johnston and Frank, 2014; Baker 2020, 247).

In his self-portrait, Domingo presents his distinct Chinese mestizo features (Santiago 2000, 83). He is dressed in the uniform of a Spanish navy ensign. The miniature, once thought lost, was later rediscovered during an audit of the Luis Araneta Collection, where it had been carefully stored inside an ostrich egg, wrapped in gold and mother of pearl, and mounted on silver.

In the early nineteenth century, inexpensive labor, largely from migrants, facilitated the growth of a broad art market. Middle-class families in urban areas particularly benefited, collecting numerous portraits of various family members. Miniatures featuring children, parents, siblings, cousins, and even deceased relatives reinforced the genre’s domestic associations. By the early nineteenth century, ivory miniatures had become affordable luxuries and cherished mementos that could be acquired at various significant moments in a family’s life. Art historian Robin Jaffee Frank (2000, xiv) traces the popularity of ivory miniatures in the 1820s to the growing importance of affection as a family value. Worn close to the owner’s body, miniatures were kept like talismans that evoke emotional closeness for generations.

The meticulous process of preparing and painting on thin sheets of ivory also reveals a sense of intimacy between artists, their subject, and their materials. The ivory sheet needed to be degreased, bleached, and ground with pumice powder. The paint, consisting of pigment, water, and binders like gum arabic and sometimes sugar candy, had to be mixed precisely (Kelly, 139). Applying watercolor to ivory was very challenging. The painter would start by lightly tracing the sitter’s outline on the ivory. Less confident artists could draw the outline on paper and place it under the transparent ivory to trace it. The painter would then color the shadowed areas of the face and background with a dark neutral shade before applying solid colors, moving from dark to light. To manage color intensity, novice painters were advised to paint the face upside down, starting from the chin and working up to the forehead, allowing the brush to naturally lighten as it ran out of paint. Such were the technical skills required of ivory painting (ibid.)

References

Johnston, Patricia, and Caroline Frank. Global Trade and Visual Arts in Federal New England. Durham: University of New Hampshire Press, 2014. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/35586.

Capistrano-Baker, Florina H. and Meha Priyadarshini, eds. Transpacific Engagements: Trade, Translation, and Visual Culture of Entangled Empires (1565-1898). Italy: Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (Max-Planck-Institut), 2020.

Kelly, Catherine. Colonial Society of Massachusetts. “The Color of Whiteness: Picturing Race on Ivory.” Accessed May 15, 2024. https://www.colonialsociety.org//node/1412.

Santiago, Luciano P.R. “Damian Domingo And The First Philippine Art Academy (1821-1834).” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 19, no. 4 (1991): 264-80. Accessed June 27, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29792065.