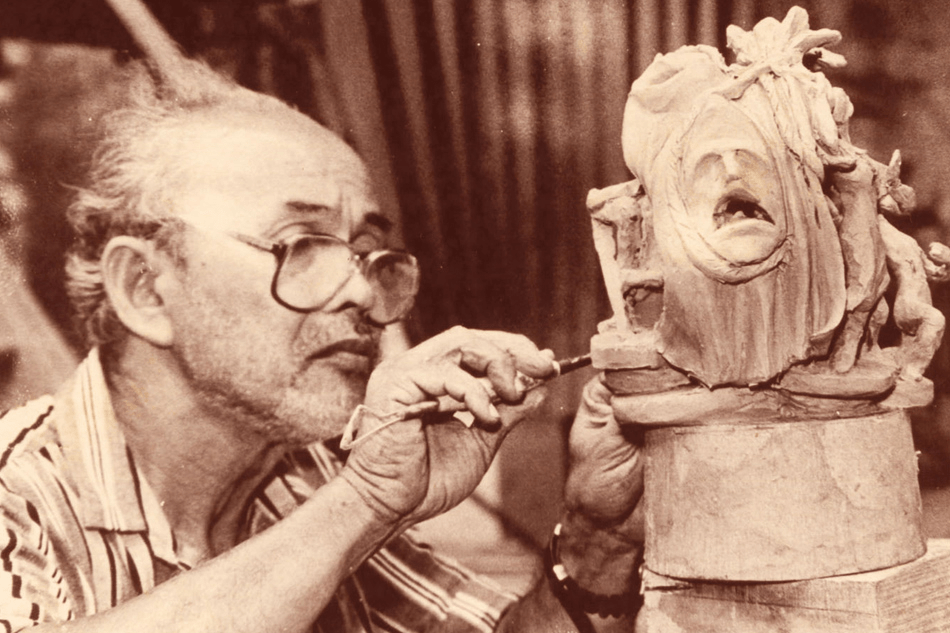

Napoleon Abueva Photo: Katrina Ventura

Napoleon Abueva’s house in Tandang Sora, Quezon City is scattered with busts of important figures, all coated in dust. Parts of the sculptor’s studio have fallen into disuse since he became wheelchair-bound over five years ago. The stroke had effectively ended his major productions. At the time, I was a sophomore at UP, and he was working on about six sculptures in the garden adjacent to the College of Fine Arts. I had met him once before—he sat silently at our fraternity tambayan, eating some dimsum. I also saw him during an awards night where he served as a judge for a student art contest I had joined. Another time, I saw him in high spirits, delivering the opening remarks at an exhibition at the Vargas Museum, joking warmly with Juvenal Sansó.

About four years ago, I visited him again to invite him as a guest to my first group exhibition. Though bedridden, Napoleon Abueva—known as “Billy” to those close to him—still made time to receive us. Last year, he even wrote a letter of recommendation for our group, supporting the Dumaguete Art Project. By then, he was already half-paralyzed and confined to bed. Billy Abueva was the first sculptor I ever admired. I learned that his modernist piece Lover’s Embrace was made around the same time as Brancusi’s version, but I preferred his—his lovers were lying on top of each other, unlike Brancusi’s, which simply stood side by side.

During one visit to his home, one of his sons helped prepare us for the challenges of creating a public installation in Dumaguete. He was tough and discerning, wanting to make sure we knew what we were doing before offering his support. I remember wondering then: what would Napoleon Abueva have said to us if he had the strength to speak?

Tonight, Billy Abueva is celebrating his 82nd birthday. Just days ago, he suffered from a ruptured bladder, and his son was calling for blood donors. I wanted to donate—just the idea of sharing my blood with a National Artist was meaningful to me—but I was out of the country. I wanted to send him a card to thank him for all his support, to tell him how his letter opened doors for our project, and how that project eventually led to a research residency in Berlin. I wanted to tell him how I studied his piece at the National Museum as a young critic-in-training. But in truth, my gratitude feels small compared to the outpouring of love from his friends, fellow artists, and family.

Billy Abueva once said that a career in the arts is “a long-distance race.” What matters, he said, is that an artist sets goals for the long haul and doesn’t get discouraged by the many trials he will surely face. Whenever I read his letter, I recall a vivid sequence of images: him pulling a rope to hoist a sculpture under the sun; him smiling in a wheelchair while viewing works by young artists; his pale face and thin hands on a sickbed, slightly waving to acknowledge our presence. Billy Abueva is the grandfather artist I wish I had—and the kind so many artists wish they had. His sculptures welcomed me to college at UP, shaded me while waiting for an Ikot jeepney, and intrigued me endlessly as I sat on a bench in front of my building. My first essay about art was about his work, in relation to that of another Filipino modernist, Jose Joya.

Tonight, he is awake, but he can no longer lift his head to see the people around him. I know he hears us—the people who came to throw him a shindig. He can probably feel the warmth of our birthday song, but he can no longer blush, can no longer return the gratitude, can barely reach out—everything now has to be sanitized. As dust gathers around his works and unfinished projects, I feel a tight grip around my heart. Even if our relationship was merely that of idol and admirer, I could not bear to look at him like this. I walked away and sneezed.

Leave a comment