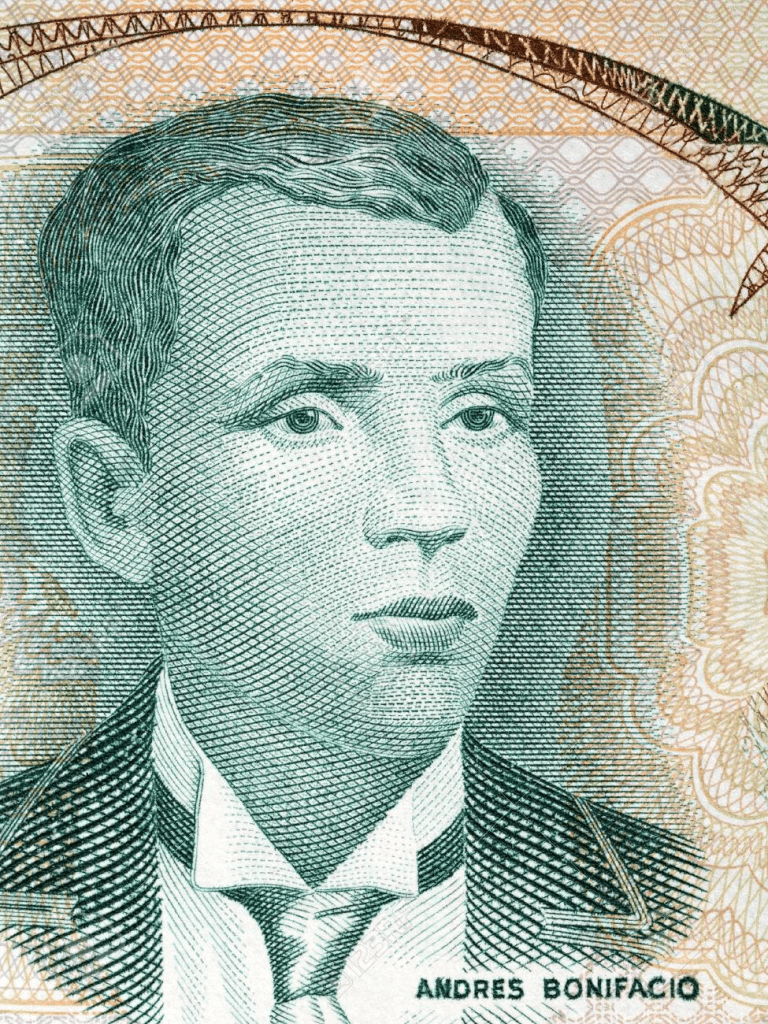

Andrés Bonifacio (1863–1897) was a Filipino revolutionary leader and founder of the Katipunan, the secret society that launched the 1896 uprising against Spanish colonial rule. Often called the “Father of the Philippine Revolution,” Bonifacio emerged from modest urban circumstances in Tondo, Manila, and rose to prominence through his ability to mobilise working-class supporters. Unlike later elite nationalist figures, his authority rested on grassroots networks and a powerful vernacular political imagination.

Within late nineteenth-century Tagalog society, talismans functioned as protective technologies that bound the body to divine sanction. For Katipuneros facing a vastly superior colonial army, the agimat offered a materialised claim to moral and spiritual protection. In this sense, Bonifacio’s reputed use of a talisman should be understood within a wider insurgent ecology in which political action and sacred power were tightly interwoven.

The anting-anting attributed to Andres Bonifacio measures approximately 2 inches by 1½ inches (5 x 4 cm). It is said to have been carried by Bonifacio during the Battle of Pinaglabanan on 30 August 1896, one week after the Cry of Balintawak and shortly after the Spanish authorities discovered the Katipunan on 19 August 1896.

The talisman bears an image of Nuestra Señora del Pilar on the obverse and Santiago de Galicia on the reverse. Such objects were believed to offer protection from harm and were commonly worn by Katipuneros, many of whom went into battle armed primarily with bolos, bamboo spears, a small number of firearms, and anting-anting.

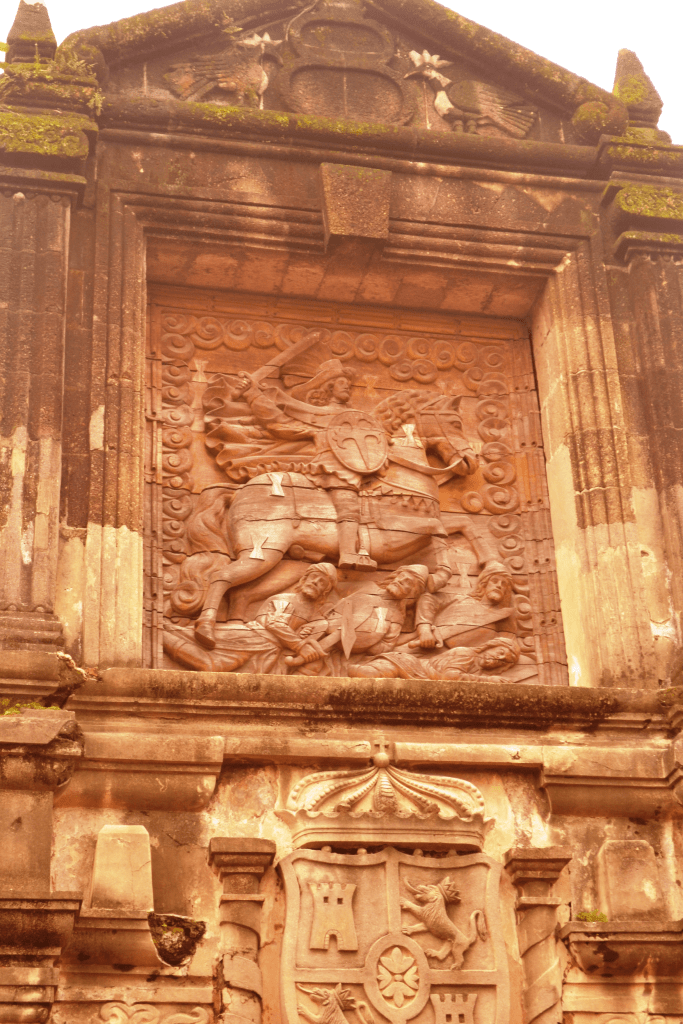

James the Great—known in Spain as Santiago—became one of the most powerful symbols of Spanish Christianity through the legend of the Battle of Clavijo, traditionally dated to 844. According to later medieval accounts, the apostle appeared on a white horse to aid Christian forces against Muslim armies, earning the title Santiago Matamoros (“Moor-slayer”). Although historians agree that the story emerged centuries after the supposed event and likely drew from later conflicts in the region of La Rioja, the image took on enormous symbolic weight during the Reconquista. Santiago was depicted as a mounted warrior, sword raised, banner bearing the red cross of the Order of Santiago, trampling defeated enemies beneath his horse. The icon fused spiritual patronage with military triumph and became inseparable from Spanish national identity.

When Spain expanded into the Americas and the Pacific, the iconography traveled with it. In the Philippines, images of Santiago Matamoros appeared in churches, chapels, and devotional altars across the archipelago, particularly in parishes dedicated to St. James in Bulacan, Pampanga, Laguna, Cavite, Batangas, Tarlac, and parts of Mindanao. His feast day on May 23 continues to be marked in some communities with processions and festivals. The figure of the mounted warrior, sword raised, remained visually consistent: white horse in motion, cloak swirling, enemies subdued beneath him.

In Manila, the most prominent representation of Santiago Matamoros is the bas-relief installed on the façade of Fort Santiago in Intramuros. The fortress, constructed beginning in 1571 and named after the apostle, served as a defensive stronghold and later as a prison during Spanish rule. The relief of Santiago, positioned above the gate, asserted both religious patronage and imperial authority at the very entrance to the colonial citadel. Although the fort was heavily damaged during the 1945 Battle of Manila, the image was later restored; a replica carved in 1982 remains in place today.

Outside Intramuros, devotion to Santiago continues in Sta. Cruz, Manila, where a chapel known locally as Santiago de Galicia commemorates the apostle annually.

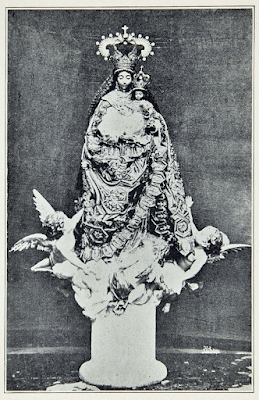

Nuestra Señora del Pilar of Manila, known locally as La Pilarica, is enshrined in Santa Cruz Church. The image has a carved mahogany body covered in engraved silver plates, with ivory heads and hands for both Mother and Child. She stands upon a pillar, recalling the tradition of her apparition to James the Great in Zaragoza in 40 AD. The pillar signifies firmness in faith and divine reinforcement in moments of crisis.

Brought to Manila by the Jesuits before 1743, the image became closely tied to the commercial life of Santa Cruz, once a wealthy mercantile district. Devotees adorned her with embroidered mantles, crowns, and diamond ornaments in gratitude for perceived miracles and economic stability. She was believed to have survived the 1863 earthquake unharmed and was secured for protection during wartime occupations. Over time, La Pilarica came to symbolize endurance amid disaster, invasion, and urban transformation, an image of protection rooted in both Spanish Marian devotion and Manila’s own layered history.

The Battle of Pinaglabanan, where Bonifacio allegedly wore the anting-anting, took place at El Polvorin, a Spanish munitions depot in San Juan del Monte. On the night of 29 August 1896, Bonifacio and his aide Emilio Jacinto led Katipunero forces toward the depot. At approximately 4:00 a.m. on 30 August, they launched a surprise attack and briefly captured the site. Spanish forces later regrouped, including the 73rd “Jolo” Regiment under General Bernardo Echaluce y Jauregui, armed with Remington Rolling Block rifles, and eventually repelled the revolutionaries.

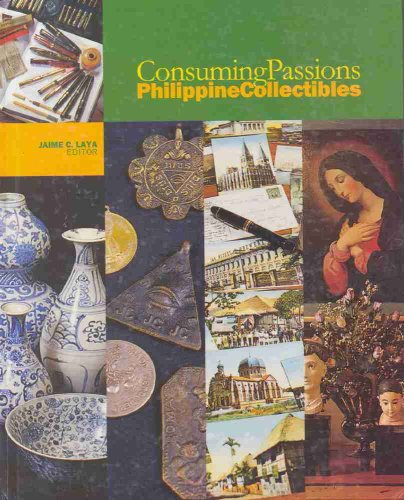

The anting-anting was offered as Lot 103 at Leon Gallery on 10 September 2016. The talisman’s documented provenance traces it to Epifanio de los Santos, who gifted it to Dr. Jose P. Bantug. It then passed by descent to Don Antonio Bantug and his heirs. The object is illustrated in Jaime C. Laya’s Consuming Passions: Philippine Collectibles (Anvil Publishing, 2003, p. 42).