In Walter Benjamin’s writing, “weak messianic power” (schwache messianische Kraft) names a fragile, non-sovereign capacity that belongs to the present to redeem the past—not by fulfilling history’s promises in a grand, theological sense, but by interrupting the dominant narrative of progress and rescuing suppressed or defeated moments from oblivion.

The phrase appears most explicitly in “On the Concept of History” (1940), especially Thesis II. Benjamin argues that every generation is endowed with a weak messianic power toward past generations. This power is weak because it does not command history or guarantee redemption; it cannot force justice to occur. Instead, it operates contingently, through acts of recognition, remembrance, and critical historical attention. Redemption, for Benjamin, is not an inevitable outcome but a task that may or may not be taken up.

Crucially, this power is exercised through historical consciousness, not political triumph. The historian—or more broadly, the subject in the present—can “brush history against the grain” by refusing the victors’ account of the past. When one recognizes a moment of past suffering as unfinished and unjust, one activates this weak messianic power. It is an ethical obligation rather than a metaphysical certainty: the past places a claim on the present, but that claim can be ignored.

Weak messianic power also explains Benjamin’s rejection of linear, progressive time. History is not a smooth continuum leading toward improvement; it is shot through with moments of danger (Jetztzeit), in which the present flashes up as a chance to redeem a past struggle. The messianic element here is not a future savior but the possibility that the present might do justice to what has been lost—through memory, citation, and revolutionary interruption.

Importantly, Benjamin’s messianism is deliberately secularized and inverted. The Messiah does not arrive to complete history; rather, human beings bear a faint, residual messianic responsibility. This aligns with his broader materialist theology: theological concepts are preserved only insofar as they can energize critique. Weak messianic power thus becomes a way to think political and historical action without utopian guarantees.

The weak messianic power is Benjamin’s name for the precarious capacity of the present to redeem the past by recognizing its unresolved claims. It is weak because it offers no assurance of success—but precisely in that weakness lies its ethical urgency.

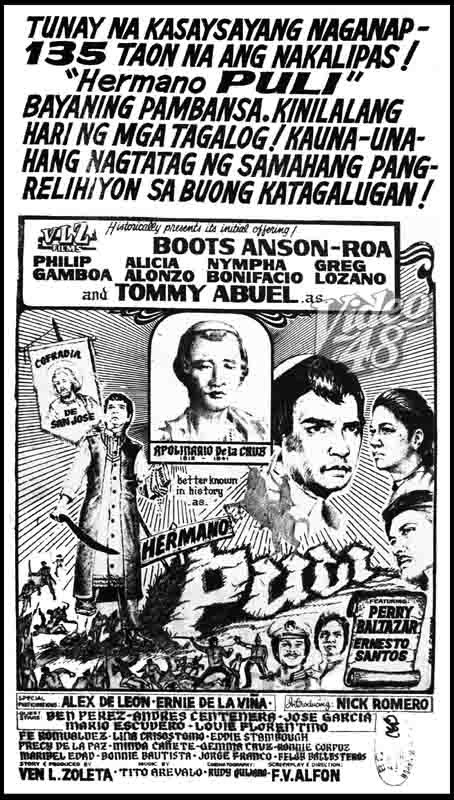

Hermano Pule

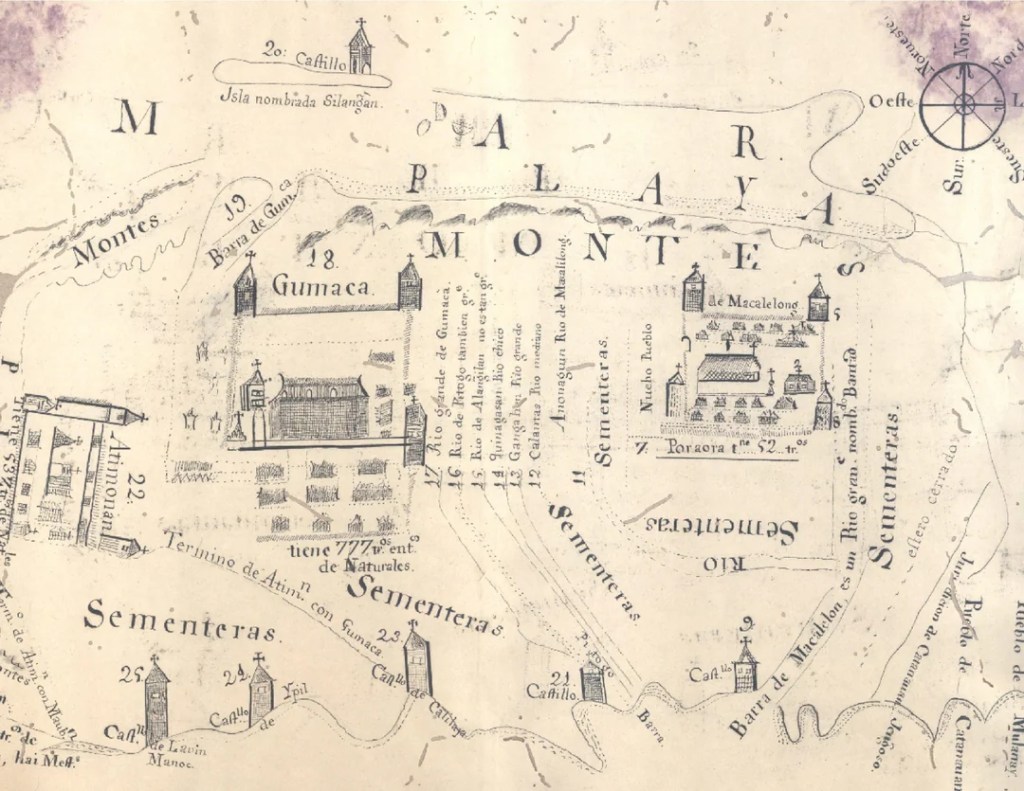

Apolinario de la Cruz (1815–1841), later known as Hermano Pule, was born in Lucban, Tayabas (now Quezon Province), to poor but devout parents. From a young age he demonstrated strong religious commitment and sought entry into the priesthood, but like most indios he was barred from ordination by the Spanish colonial Church, which reserved clerical advancement for Spaniards and criollos. Unable to become a friar, he joined the San Juan de Dios hospital order in Manila as a lay brother, where he acquired the name “Pule,” a Hispanized contraction of Apolinario. After leaving the hospital order and returning to Tayabas, he founded in 1832 the Cofradía de San José, a lay religious confraternity dedicated to Saint Joseph and explicitly open to native Filipinos. The confraternity combined orthodox Catholic devotion with local forms of discipline, prayer, and communal organization, and it spread rapidly across Tayabas, Laguna, and nearby provinces, attracting thousands of followers who found in it both spiritual dignity and social belonging denied by the colonial Church.

Colonial and ecclesiastical authorities viewed the Cofradía with suspicion, repeatedly ordering its dissolution on the grounds that it lacked clerical supervision and threatened public order. Pule attempted to secure official recognition by appealing to Church authorities in Manila, but his petitions were rejected, reinforcing the racial boundaries that structured colonial Catholicism. By 1841, mounting repression pushed the movement into open confrontation. After a skirmish between Cofradía members and colonial troops at Alitao, the Spanish government declared the confraternity seditious. Pule was captured, subjected to public humiliation, and executed by firing squad on 4 November 1841, after being forced to witness the execution of several followers. His body was mutilated and displayed as a warning, and the Cofradía was violently suppressed. Although erased for decades from official histories or reduced to a footnote of “religious fanaticism,” Hermano Pule’s life stands as one of the earliest and most consequential episodes of indigenous religious resistance under Spanish rule, revealing how colonial power policed spiritual authority and how popular devotion could become a site of collective dissent long before the rise of formal nationalist movements.