When Asedillo premiered in 1971, Ferdinand Marcos was tightening his grip on the republic, and the air in Manila was thick with student marches, labor strikes, and the metallic aftertaste of tear gas. Celso Ad. Castillo’s film—produced by and starring Fernando Poe Jr.—could have been mistaken for another action vehicle designed to confirm FPJ’s legend as the incorruptible man of the masses. Yet Asedillo remains one of the most serious and carefully structured nationalist films of its decade, a work that straddles the populist appeal of commercial cinema and the moral gravity of political allegory. It is both a biography and a fable about how a teacher becomes the conscience of a colonized nation.

The historical Teodoro Asedillo (1883–1935) was born in Longos, Laguna, and educated under the American colonial school system. He worked as a public-school teacher who openly criticized the use of American textbooks, arguing that his Filipino students could not learn meaningfully from foreign-authored materials. His refusal to conform led to his dismissal and marked the beginning of a lifelong conflict with colonial authorities. After serving briefly as a municipal police chief, Asedillo became involved with peasant movements such as the Anak-Pawis (Children of Toil) organization in Laguna and Tayabas, where he advocated for agrarian justice and workers’ rights. Eventually, he led an armed rebellion in the Sierra Madre against local elites and abusive officials. The American colonial government branded him a tulisan (bandit), but in oral tradition he became a Robin Hood figure—a teacher who, betrayed by the system, turned his lessons into a struggle for justice. He was killed by the Philippine Constabulary in December 1935, shortly after the founding of the Philippine Commonwealth. Celso Ad. Castillo’s 1971 film Asedillo traces this transformation with documentary precision and the intensity of legend.

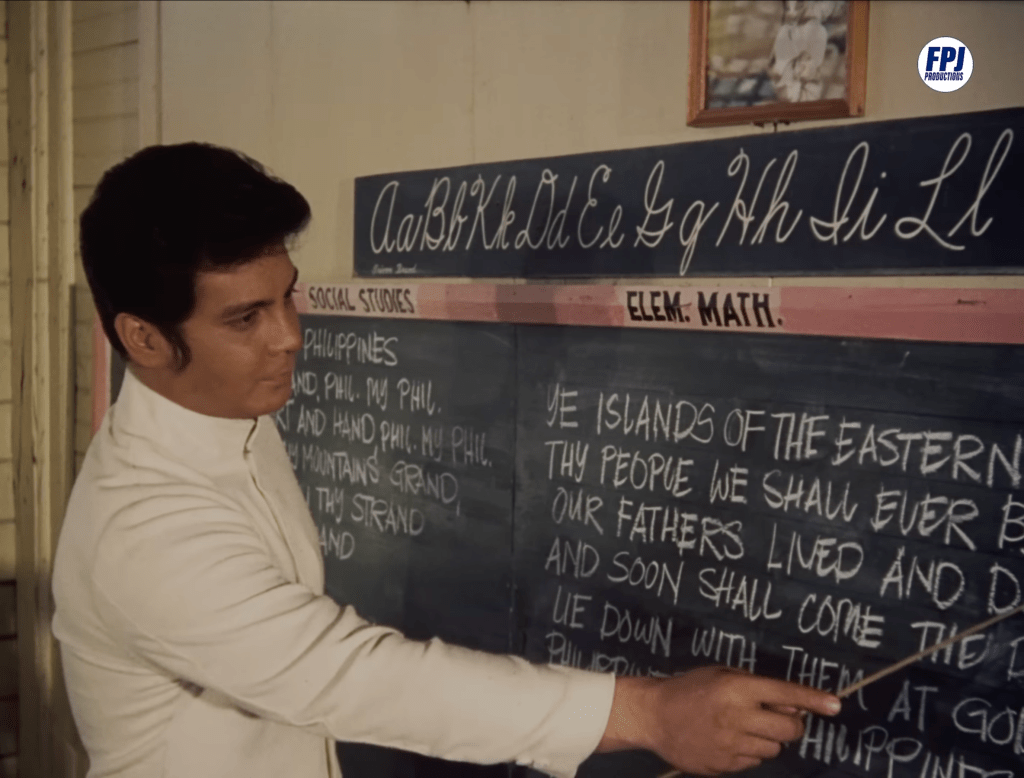

In the first major dialogue sequence, Asedillo refuses to continue using American textbooks: “Tatlong taon na akong nagtuturo sa paaralang ito… sapagkat ang ginagamit nilang libro ay galing sa ibang bansa at sinulat ng mga banyaga” (“I’ve been teaching in this school for three years… and the books we use come from other countries and are written by foreigners”). When his superior, Mr. Mendez, insists on obedience to orders, Asedillo responds, “Ang pag-aaral ay hindi lamang sa pamamagitan ng libro, ito’y nasa pang-unawa” (“Learning does not come only from books; it lies in understanding”). This scene establishes his intellectual independence and commitment to a Filipino-centered education.

Publisher: The University of the Philippines Press

Resigning from teaching, he accepts a post as police chief in Paete. To his wife Maria, he insists there is no contradiction between the two professions: “Ang dalawang gawaing ’yan ay parehong nakalaan sa paglilingkod sa bayan” (“Both kinds of work are equally devoted to serving the nation”). His honesty and refusal to participate in corruption make him a political threat. A local politician warns, “Ang taong katulad ni Dodo ay mapanganib” (“A man like Dodo is dangerous”), recognizing that his integrity and popularity among the poor could lead to unrest.

Asedillo is soon accused of theft. When the mayor confronts him, he protests, “Ang taong nakikita mo ngayon ay patay na! Sapagkat sinugatan nila ang aking karangalan” (“The man you see before you is already dead! They have wounded my honor”). This line signals his moral break with the system. Dismissed and hunted, he joins his cousin Pablo’s Anak-Pawis movement, a federation of workers and farmers. In one exchange, Pablo persuades him to join the collective struggle, but Asedillo cautions patience: “Hindi masarap kainin ang manggang hinog sa kalburo… Hintayin mo manilaw ang mangga sa puno, bago mo pitasin” (“A mango ripened with lime is not sweet… wait for it to yellow on the tree before picking it”).

The film introduces a significant object—the agimat (amulet)—given to him by Rosing, a village woman who visits him secretly. “Ang rikuwerdong ito ay minana pa ng nasira kong ama sa aking tata. May kasama rin dasal ang rikuwerdong ito… isang agimat na magliligtas sa panganib sa sino mang may suot nito” (“This keepsake was inherited by my late father from my grandfather. It comes with a prayer… an amulet that will save whoever wears it from danger”). The agimat is worn visibly around his neck for the rest of the film, serving as a visual emblem of his transformation from teacher to folk hero.

From his mountain hideout, Asedillo explains his cause to the townspeople. “Ako raw ay magnanakaw,” he declares in a public speech, “Oo, ako’y magnanakaw! Pero hindi ko ninanakaw ang mga butil ng kanin na isusubo na lamang sa bibig ng mga mahihirap” (“They say I am a thief. Yes, I am a thief! But I do not steal the grains of rice already at the mouths of the poor”). His self-defense reframes him as a moral rebel rather than an outlaw. “San Antonio! Kayong mga tao ang batis, ang ilog, at ang dagat! Ako ang isda!” (“San Antonio! You people are the spring, the river, and the sea! I am the fish!”), he proclaims, identifying himself with the collective body of the people.

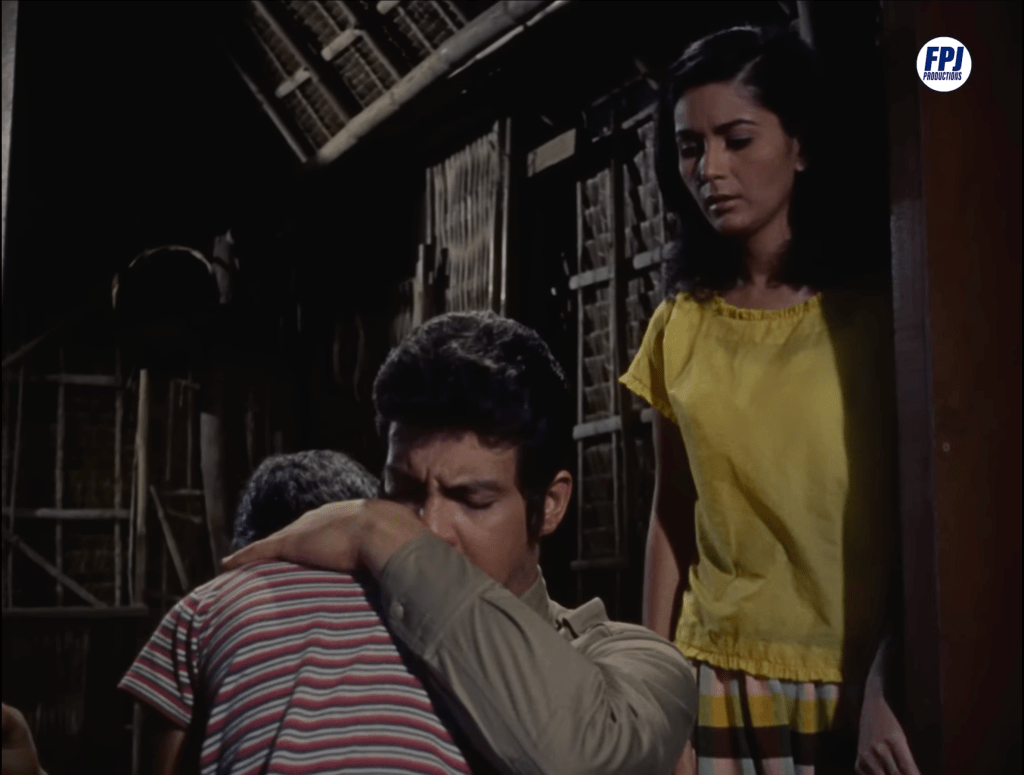

Asedillo’s wife Maria dies of illness, and before her death, she tells him, “Kung saka-sakali lamang na mawawala ako, ipangako mo sa akin… kapag mag-aasawa kang muli, ay si Hulya ang piliin mo” (“If I should pass away, promise me this… if you remarry, choose Hulya”). Hulya, his former lover, becomes guardian to their child. In a later scene, she begs him to give up the fight: “Ang kailangan ko ay isang asawa… ang kailangan ng iyong mga anak ay isang ama, hindi isang puntod” (“What I need is a husband… what your children need is a father, not a grave”). Asedillo replies, “Hindi ko maaaring pagtaksilan ang pananalig ng mga taong umaasa sa akin” (“I cannot betray the faith of those who depend on me”).

Later, a government officer conveys President Quezon’s message: “Nakausap ko si Pangulong Quezon. Sumuko ka lang at pipilitin niyang unawain ang iyong katayuan” (“I have spoken with President Quezon. If you surrender, he will try to understand your situation”). Asedillo responds, “Hindi ako humihingi ng dugo ni Juan Dela Cruz. Maliit na bagay lamang ang hinihiling ko para sa kapakanan ng mga mahihirap” (“I do not ask for the blood of the common Filipino. What I ask is a small thing—for the welfare of the poor”). His refusal to surrender becomes the film’s moral conclusion.

In the climactic scene, surrounded by constabulary forces, Asedillo delivers his final address: “Ang krus na ito ang magiging bantayog ng ating simulain… Tayong mauunang taong tutubo sa punong ito, at tayo rin ang unang dahong malalagas. Subalit patuloy na uusbong… Kailanman ay hindi nila maaaring kitlan ng buhay ang aking simulain” (“This cross will stand as the monument of our cause… We are the first who will grow on this tree, and we will also be the first leaves to fall. But it will keep sprouting anew… They can never take the life of our cause”). He is killed shortly after, still wearing his agimat. As his body lies motionless, the nationalist hymn plays in full, linking his death to a national awakening.

Asedillo is structured as a linear biographical film that mirrors the logic of martyrdom common to nationalist cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The narrative divides his life into three phases—teacher, public servant, and rebel—each defined by a refusal to compromise principles. The dialogue-driven script emphasizes the transition from intellectual dissent to armed resistance.

The classroom sequence foregrounds the ideological critique of colonial education, encapsulated in Asedillo’s line, “Ang pag-aaral ay hindi lamang sa pamamagitan ng libro” (“Learning does not come only from books”). This scene functions as the origin point for his later revolt; rebellion begins as pedagogy. Castillo stages it in static frames, focusing on FPJ’s composure and measured tone rather than anger, underlining that moral conviction precedes violence.

The agimat provides a second narrative thread. Given to Asedillo midway through the film, the amulet operates both as personal charm and as national metaphor. It symbolizes moral protection and continuity of belief, appearing in nearly every scene until his death. The object visualizes what he later articulates verbally: “Ang ililibing nila sa puntod ay ang katawang lupa lamang ni Asedillo” (“What they will bury in the grave is only Asedillo’s earthly body”).

Cinematographer Sergio Lobo frames the mountain as both refuge and metaphor. The movement from the flat geometry of the classroom to the rugged topography of the Sierra Madre visually parallels Asedillo’s transformation from reformist to revolutionary. Restie Umali’s score alternates between martial brass and choral renditions of “Philippines, My Philippines,” reinforcing the connection between sacrifice and national memory.

FPJ’s performance is restrained, marked by minimal gesture and direct delivery. His Asedillo speaks in declarative sentences—calm, didactic, and unwavering. Castillo avoids melodrama, opting instead for clarity and repetition of moral lines.

Asedillo remains notable for merging historical realism with folk iconography. Its use of the agimat, nationalist rhetoric, and consistent appeal to karangalan (“honor”) situate it within both cinematic and political histories of the early Marcos period. The film transforms a provincial insurgent into an archetype of incorruptibility and links education, faith, and rebellion through loud knocks of conscience.