Herbert Johnson Museum

Jan 25, 2025–June 8, 2025

Ithaca, NY

In her artist statement for Portrait in Six Dimensions (1973), Suzi Ferrer (1940–2006) described the installation as emerging from her “continuing concern with the relation of the individual to society,” specifically addressing “female stereotypes and role-playing, or perhaps, what this society expects of women, and how they are viewed in it.”

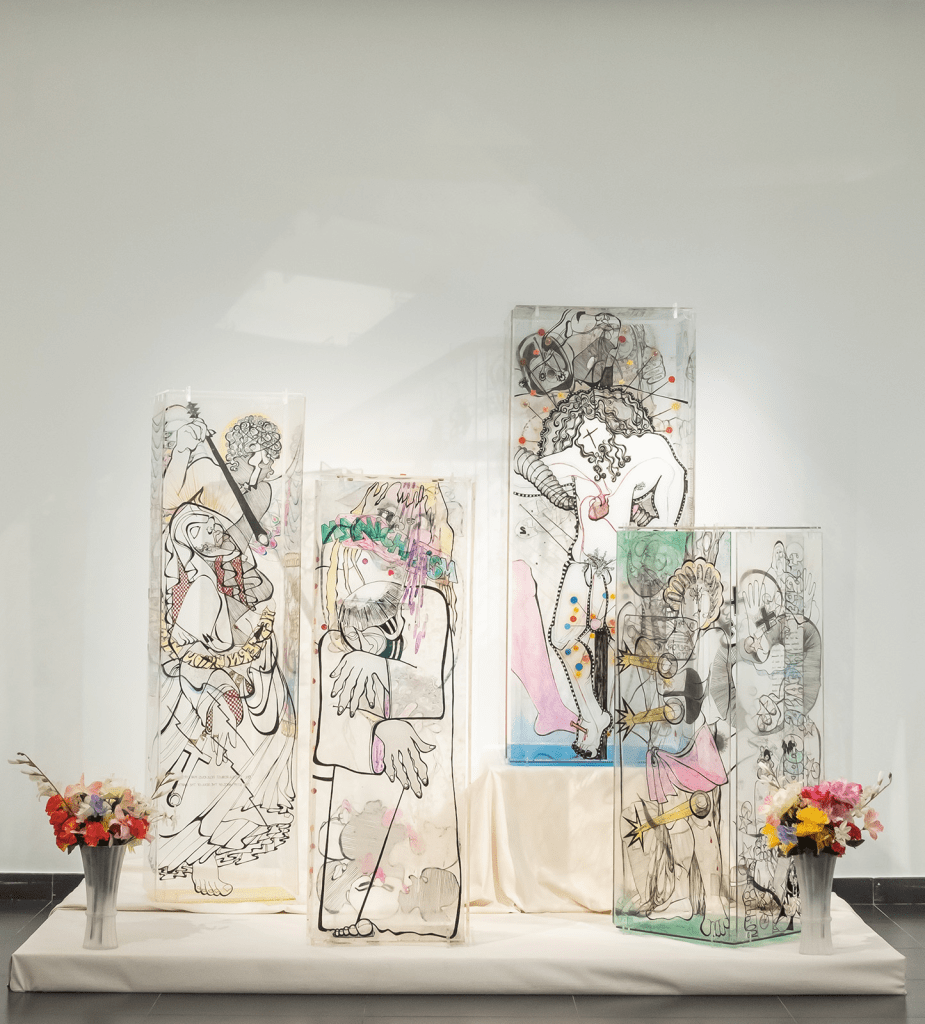

Upon entering the installation, the viewer is struck by the visceral impact of Plexiglas silhouettes hanging by their necks, swaying slowly to music evocative of a 1930s girlie show. The cast shadows of these ‘victims,’ hanging by their necks, heighten the bizarre atmosphere, shifting between the humorous and funky, and the grotesque and macabre. Each represents a patriarchal archetype of femininity, trapped in a performative act of submission. Their suspension literalizes the condition of women’s roles under the dominant order—caught between social expectation and artistic defiance.

Ferrer’s feminist radicalism—her bold embrace of the erotic, her playful and subversive use of spectacle, and her unapologetic challenge to power—renders her work inseparable from her identity.

Yet despite its striking intensity, Ferrer’s work nearly vanished from art history. Her retrospective, originally staged at the Museo de Arte y Diseño de Miramar, challenges the assumption that artistic recognition follows a natural trajectory. Curator Melissa M. Ramos Borges undertook an almost archaeological endeavor to resurrect Ferrer’s installations from the 1970s—works that had been shown only once or twice before fading into obscurity.

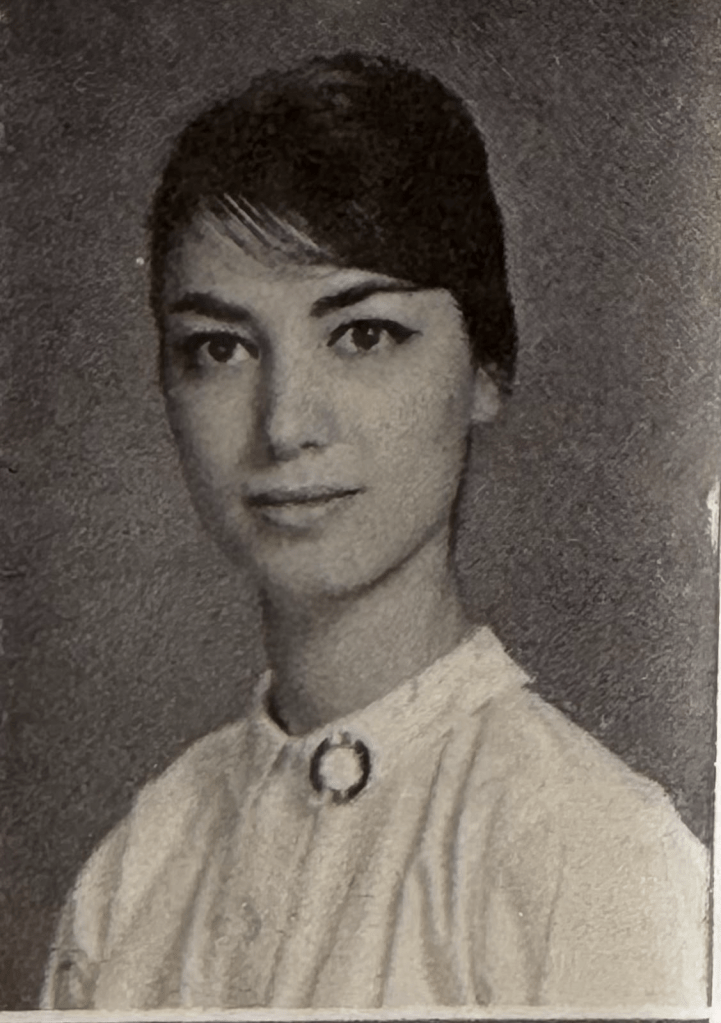

For Ferrer, this exhibition at the Johnson Museum marks a homecoming. A Cornell alum (Class of 1962), she fully embraced the avant-garde movements that captivated Cornell art students during her time, including Abstract Expressionism, Happenings, and early Conceptual and Performance art. Engaging with these radical currents, she pushed the boundaries of installation and feminist art.

A New York City native, found her most radical voice in Puerto Rico, where she spent a decade producing some of the most transgressive feminist art of the 1970s. She was a prominent fixture in Puerto Rico’s art scene, exhibiting in commercial galleries and national museums. Despite her prolific career—well-documented in San Juan newspapers, exhibition catalogs, and reference books—Ferrer’s work faded from art historical memory when she relocated to California in the mid-seventies.

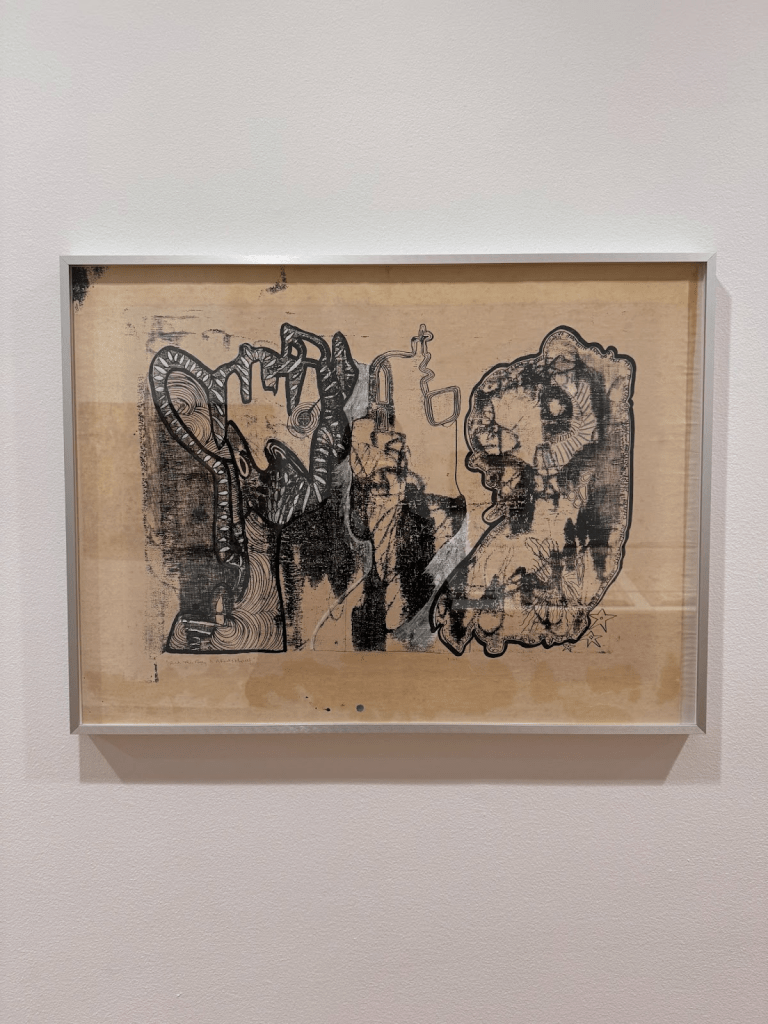

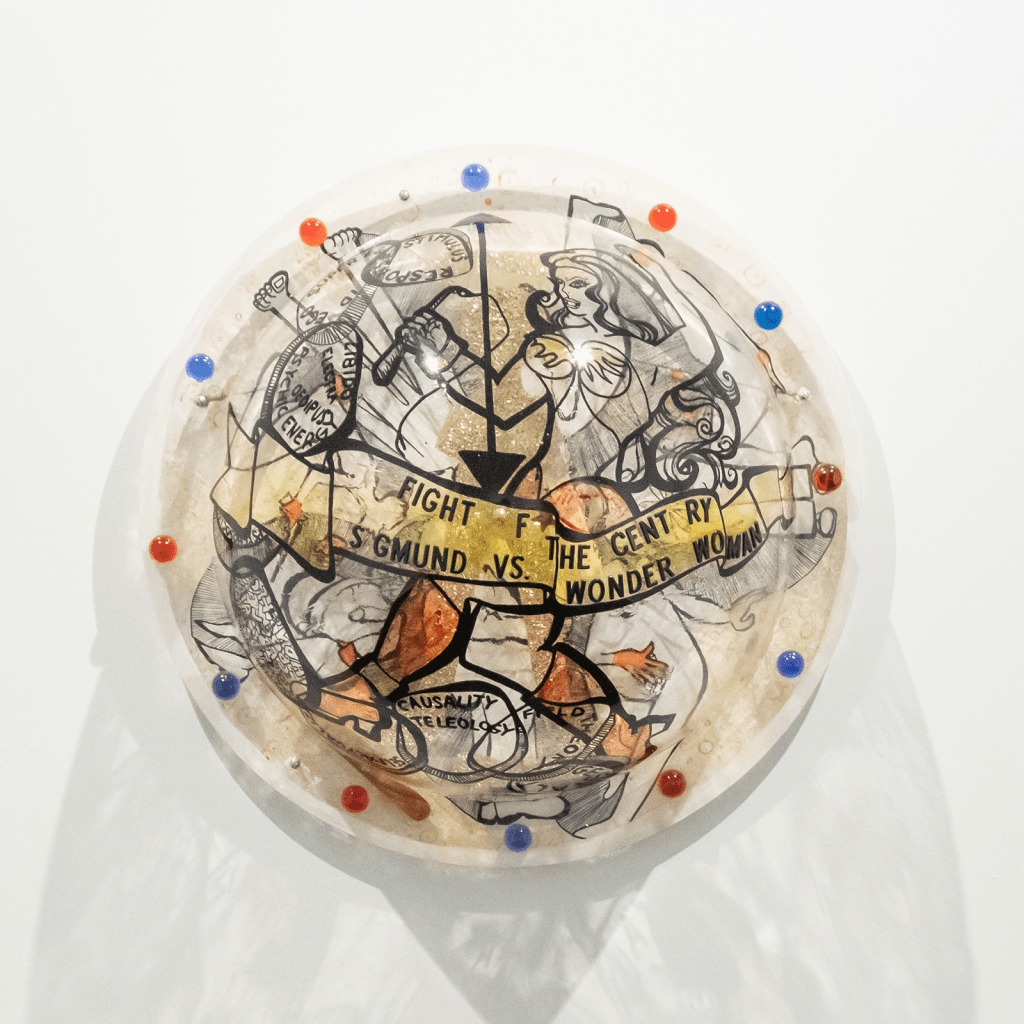

The exhibition which serves as a long-overdue reassessment of her contributions, follows a chronological path, revealing the rapid evolution of Ferrer’s practice. Her mid-1960s works, steeped in Art Brut, bear the imprint of Jean Dubuffet—but with dripping paint, earth tones, and a visceral engagement with materiality. By the 1970s, however, her work had undergone a profound shift toward a feminist, decolonial, and overtly political aesthetic. She embraced antiwar critiques and mined Catholic iconography to subvert its power over Puerto Rican society and culture. The Nudelman Altarpiece (1972), a collection of suspended Plexiglas paintings, reimagines religious scenes by collapsing the sacred and the profane—St. Teresa in ecstasy, St. Anthony’s temptation, St. Sebastian’s martyrdom—through the lens of hypersexualized bodies. Wide hips, exaggerated breasts, and explicit poses coalesce with floods of text, a motif that recurs throughout Ferrer’s work.

Ferrer’s artistic career was brief, bound primarily to her years in Puerto Rico. She was, in many ways, an artist whose work existed on the periphery of multiple art worlds—recognized, yet never fully absorbed by the institutions of her time. While no one can fully anticipate how any artist can occupy a central place in any canon, curators of the Johnson Museum show contend that art history is sometimes shaped by the smallest particles—those that, despite the tide, refuse to sink.

It was in the early 1970s, when Ferrer’s work embraced a feminist perspective, that she produced her most sophisticated and confrontational work: immersive, multi-sensory installations that embodied female experience across public and private spheres. These pieces grappled with gender roles, sexual liberation, body politics, and the history of art itself. Ferrer worked fluidly across mediums—drawings, paintings, graphic works, and installations—while consistently centering feminist themes that bore the influence of Pop Art, local Puerto Rican artists, the counterculture, and Jungian psychology. The exhibition contextualizes her practice with archival materials, including her lacquered wood framed Cornell diploma which students found amusing. Newspaper clippings, exhibition catalogs, photographs, and Ferrer’s own annotations, which provide critical insights into her conceptual concerns and creative processes.

Ferrer’s biographical trajectory intersects with key milestones in the feminist movement. She was born in 1940 and came of age as Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1953) was propelling second-wave feminism. Her studies in visual arts at Cornell, performances on Broadway, and exhibitions at the A.D. White Art Museum (now the Johnson Museum)—prepared her later experimentations in feminist artmaking. At the time of her move to New York, marriage, and relocation to Puerto Rico, feminist thought grew traction with the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) and the founding of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966.

Ferrer’s presence in Puerto Rico’s art scene was immediate and impactful. By 1966, she had participated in the Experimentos serigráficos at the Galería Colibrí, where she was the only woman represented, and held her first solo exhibition at Casa del Arte. She won first prize in graphics at the IBEC art competition in 1967, but her growing prominence did not shield her from the institutional sexism of the period. New York art critic Jay Jacobs, in his 1967 review “Art in Puerto Rico” for ARTgallery Magazine, dismissed Ferrer’s work with a patronizing remark: “a talented but immature collagist who has yet to produce a piece as good looking as the one engineered by her parents.”

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Ferrer’s practice had evolved toward explicitly feminist critiques. Her second solo exhibition at Casa del Arte in 1969 included Literary Assassin, a painting that confronted the intersections of gender, literature, and violence. By 1971, she had developed her Plarotics series—drawings on Plexiglas—exhibited in her third solo show. That same year, ArtNews published Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” a question that haunted Ferrer’s career in real time. In a 1971 interview with El Nuevo Día, she remarked, “If I were a man and painted the same way, they’d say, ‘Oh, what a man.’ They wouldn’t say I was edgy or brazen or anything like that. I’m a woman, and I love men, but I find a certain prejudice against women.”

Ferrer’s feminist interventions continued throughout the 1970s, aligning with global feminist activism. In 1972, she exhibited at the Second Latin American Print Biennial of San Juan, showing Ream Clean and Oh, Sensuous Woman, Oh. That same year, Ms. Magazine published its first independent issue, featuring Wonder Woman on the cover, marking the mainstreaming of feminist discourse in American culture.

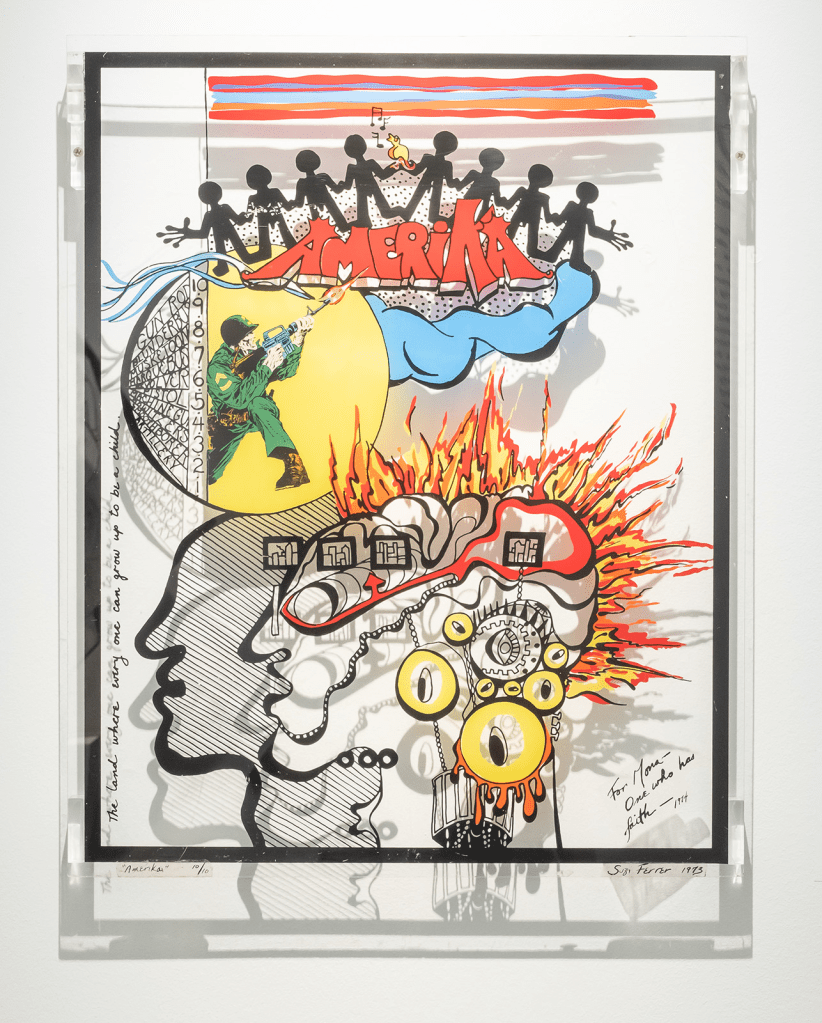

Her later years saw her engage in experimental media, working with serigraphy and installation, while continuing to push against institutional exclusions. By 1974, she had exhibited Captain Amerika and Self-Portrait I & II in the 3rd Biennial of Latin American Graphics. In 1975, she participated in the Women on Women video series alongside May Stevens, Faith Ringgold, and Kate Millett, documenting feminist artists’ contributions. However, by the mid-1970s, she transitioned away from Puerto Rico’s art scene, moving to San Francisco, where she took on roles in cultural promotion and media production.

In 1982, she directed the short film Smarkus and Company, followed by the Emmy-nominated Destined to Live (1988), a documentary on women recovering from breast cancer, which won the Humanitas Award. She later worked as a screenwriter, producing In Defense of a Married Man (1990), before moving into television production as an executive at Disney and Warner Bros. Despite her success in the media industry, her visual art practice remained overshadowed by the art world’s historical amnesia toward feminist artists.

Ferrer’s work, once marginalized, is now resurfacing at a moment when the questions she asked—about gender, power, and autonomy—feel more urgent than ever. Many of her works were exhibited only once or twice before disappearing into storage, abandoned by institutions that overlooked their significance. Curated by Andrea Inselmann at the Johnson Museum, Ferrer’s works take over the Moak, Class of 1953, Schaenen, Gold, and Picket Family Video Galleries. Cornell joins the ongoing effort to restore Ferrer’s rightful place in the canon—one in which female artists who dared to challenge gender norms are given their due recognition. The provocative questions her work raises about the place of women in a patriarchal society are especially resonant today.