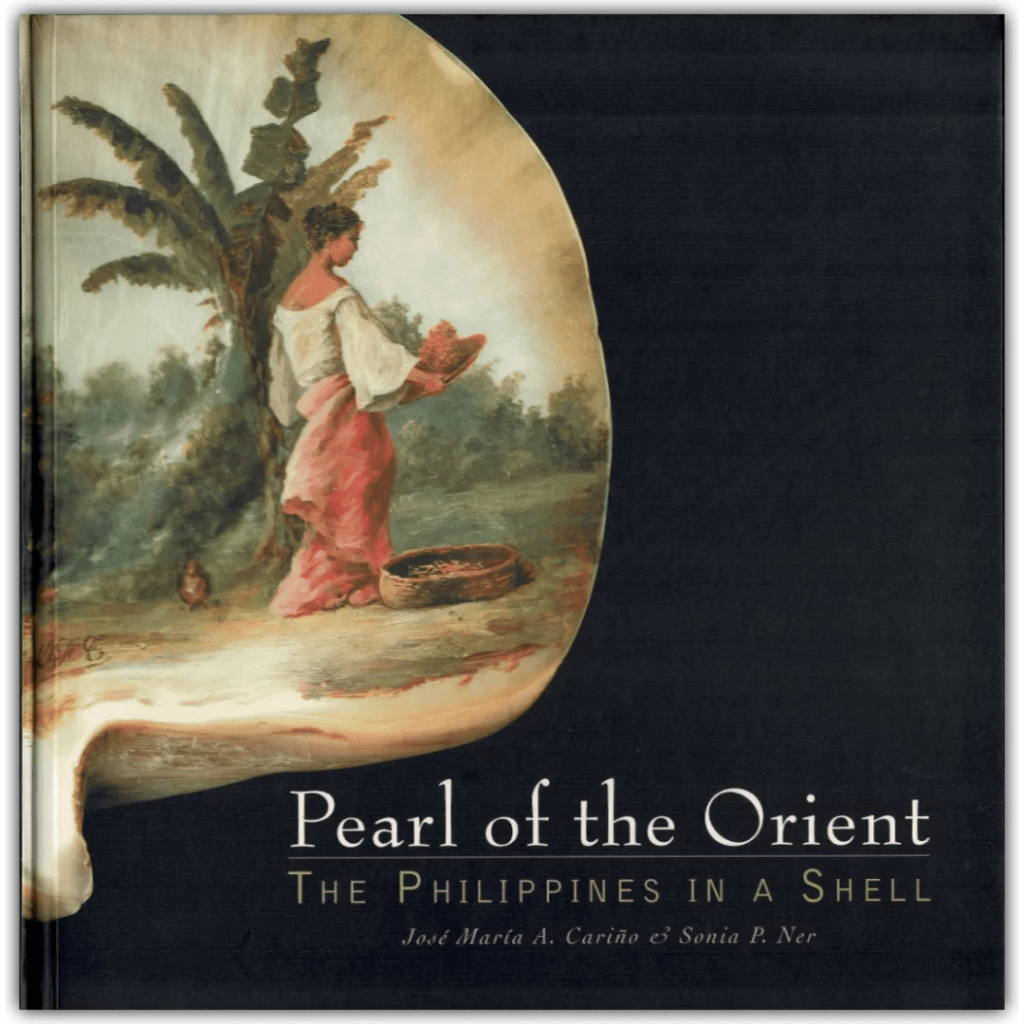

Cariño, José Maria A., and Sonia P. Ner. Pearl of the Orient: The Philippines in a Shell. Manila: Arts Mundi Philippinae, 2007.

In Pearl of the Orient: The Philippines in Shell (2007), co-authors Sonia P. Ner and Jose Maria “Jomari” Cariño bring to light an overlooked medium of 19th-century Philippine art—paintings and carvings on Pinctada maxima shells, which encapsulate the era’s cultural narratives. This collection includes works by prominent Filipino artists such as Juan Luna, Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, and Félix Martínez, as well as Spanish artists Javier Gómez de la Serna and Francisco Verdugo y Bartlett. The shells offer detailed glimpses into Philippine life under Spanish colonial rule, from architectural nuances in the bahay kubo to clothing styles, thus serving as a visual archive of the time.

Ner explains the artistic and historical significance of these shells, which until now were often disregarded as tourist trinkets. She asserts that these detailed depictions offer material insights into 19th-century Filipino life, such as the diversity of the bahay kubo structure and the various forms of traditional attire. These shells transcend their ornamental nature, presenting valuable documentation of cultural and societal dimensions that might otherwise be lost to history.

In an intriguing revelation, the authors describe their discovery of two rare shell paintings possibly created by the Philippine national hero, José Rizal. The provenance of these shells unfolds like a detective story, replete with elements of chance, intrigue, and painstaking research. According to Ner, the shells likely originated in Dapitan, where Rizal was exiled, as Pinctada maxima are native to the island. Additionally, the scenes depicted on the shells correlate with Rizal’s writings about Dapitan. A fortuitous connection with a Barcelona shopkeeper, who sold Cariño two letters penned by Rizal, brought the shells to his attention, sparking a quest for verification.

The partnership between Ner and Cariño began in 1994 in Madrid, where they connected over their shared passion for Philippine art and history. Cariño, the son of a former Philippine ambassador, had cultivated an early interest in art and, upon entering the foreign service, strategically positioned himself in Spain to access Filipino artworks from the colonial period. His meticulous methods involved establishing connections with descendants of Spanish officials, gradually gaining their trust through frequent visits and gifts from the Philippines. This network enabled him to acquire notable works, including pieces by Luna and Hidalgo, despite his initial lack of expertise in art collection.

Meanwhile, Ner’s journey into Philippine art began through her roles as an academic, researcher, and curator. As director of the Ayala Museum, she helped Cariño access research materials, nurturing his interest in Filipino art. Her persistence led Cariño to publish on Philippine art history, beginning with his 2002 book on Jose Honorato Lozano, which garnered accolades from the Manila Critics Circle.

Their shared passion led to a collaborative scholarship, yielding works like Album, Islas Filipinas 1663–1888, a book that received recognition from the Manila Critics Circle in 2004. Pearl of the Orient represents a culmination of their research journey, inspired by Ner’s fascination with shell art—a medium she first encountered in a Viennese museum in 1984. Her initial interest in shell painting eventually merged with Cariño’s burgeoning collection, resulting in a richly contextualized study of these shells.

Through scientific analysis, the authors sought to substantiate their attribution of the Rizal shells. Cariño enlisted forensic testing in Europe, demonstrating a commitment to elevating standards of art authentication in the Philippines. The results confirmed that the paint on the shells was from the late 19th century, supporting their historical authenticity. However, the authors remain open to debate, challenging skeptics to present evidence against the Rizal attribution.