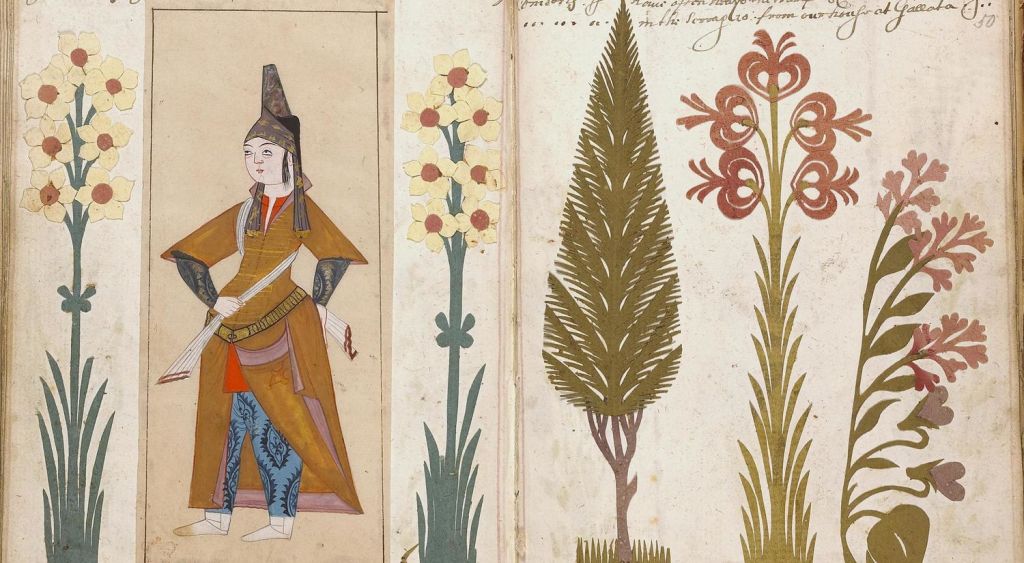

This brilliant short visual essay on Things that Talk has resurrected a forgotten facet of one of Western art’s most iconic pieces, Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl earring. Most standard scholarship does not mention this except in a brief mention in Encyclopedia Brittanica and an indirect reference to Dutch trade in the far east in Vermeer’s hat. Painted during what historians would later designate as the Dutch “Golden Age,” the Girl embodies Vermeer’s artistic vision—a composite figure shaped by his imagination and perhaps inspired by other women in his life, or a mixture of both. This “tronie” does not focus on a specific sitter’s identity, as a portrait would; instead, it captures a generalized character dressed in Ottoman-style clothing, symbolizing a fusion of cultural elements. The Dutch Republic and the Ottoman Empire shared a diplomatic rapport, with the Ottomans being the first to recognize Dutch independence from Spain, a relationship subtly reflected in Vermeer’s choice to incorporate Ottoman aesthetics in his Dutch artwork.

With her turban (fig. 2 and 3), Vermeer imbues his Girl with a worldly identity, signifying her owner’s awareness of cultures beyond the Netherlands and a Dutch tolerance for foreign influences. Her image invokes both an imperial alliance and the burgeoning status of the Dutch Republic as a global power. However, as we trace her journey through history, her identity adapts, moving from cultural hybridity to a nationalist emblem.

In 1881, Victor de Steurs and A. A. de Tombe rediscover the Girl at an auction at The Hague’s Venduhuis der Notarissen, a time when the Netherlands sought symbols of its “Golden Age” to reinforce a national identity rooted in classical high culture. De Tombe, recognizing the neglected painting as a Vermeer, realizes her value as a testament to Dutch cultural heritage. Consequently, her associations with the Ottoman Empire recede, her image becoming reappropriated as part of the Dutch cultural canon. She is no longer a figure of tolerance or cosmopolitanism; instead, her status as a Vermeer positions her as a symbol of Dutch nationalism and cultural sophistication, reflecting an idealized version of Dutch identity. Her Ottoman connections are erased, with her turban even mistaken for blonde hair. This nationalist recontextualization underscores her symbolic flexibility, shaped by the political and cultural shifts surrounding her.

In 1902, the Girl finds a permanent home in the Vermeer Room of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, solidifying her role in the Dutch national narrative. The Mauritshuis itself, a former residence of Dutch Brazil’s governor Johan Maurits, is steeped in colonial associations. Funded by colonial exploitation, the museum and its collection reflect the complex histories of Dutch imperialism. Here, the Girl’s pearl—previously a symbol of wealth—takes on new meaning within the Mauritshuis’s colonial setting. Pearls, often sourced from tropical colonies, were fashionable among European elites and serve as a reminder of the colonial legacies embedded in Dutch “Golden Age” narratives. The improbably large pearl in Vermeer’s painting thus becomes emblematic of both the allure and the exploitation underpinning this era.

Today, the Girl with a Pearl Earring has been reinterpreted and commodified, appearing on tote bags, T-shirts, and even rubber duck souvenirs in the Mauritshuis gift shop (figs. 3 and 4). Her image greets travelers at Schiphol Airport, a fixture in Dutch national identity and a quintessential stop for tourists. This modern appropriation continues to leverage her malleable identity, adapting her to contemporary narratives of cultural heritage and tourism. Beyond representing a narrow Dutch identity, she symbolizes a hybridity within Dutch culture—a blend of external influences that is often overlooked. In her enduring gaze, she invites us to reconsider Dutch identity not as insular but as a dynamic entity that has long incorporated and absorbed the influence of others. In this way, she remains an enigmatic yet powerful figure, both reflecting and challenging the legacy of Vermeer’s time and beyond.