The following article is a response to the curatorial notes by Jay Ticar for Whether you hear it or not exhibit at Altromondo Chino Roces which ran from October – November 2019

One of the earliest things that came up with my discussions with Jay Ticar, the artist-curator of this exhibition, was the statement that “sound art is not music”, or that “sound art and music are not the same.” I became inquisitive of this statement: What is gained by differentiating one from the other? Both are perceived similarly. Both are subsumed in the term Zeitkunst, used by Theodor Adorno to mean art governed by the laws of time. As an intangible art form, without physical aspect, music composition offers the artist a model that does not reference any physical entity. Composers looked to the mathematical abstraction of musical aesthetics to establish an art language intrinsic to the medium of music. Sound art is an experimental field that grew out of and is in constant dialogue with its origins in music but is not limited by it. Sound artists who come from disciplines such as painting and photography had recourse to the language and concepts of music to create abstractions for which there is yet no independent language within these imagemaking disciplines. The result is art that diverts emphasis away from the mimesis we find in traditional visual arts. But this practice is not yet understood as sound art.

The practice of Jay Ticar as an artist and curator examines the rudiments of Zeitkunst in order to produce sound art and instigate engagement of it as a curatorial springboard. Whether you hear it or not takes the problematic relationship between music and sound art a step further by reconsidering hearing or aural perception as a constructed characteristic of sound art. “There are sounds that we cannot hear,” is a statement of scientific fact that has become Ticar’s curatorial admonition to renew our approaches as artists even as some of us come into this as outsiders. This intervention echoes in the entwined history of music and sound art.

When musicians in the 20th century realized that the traditional language of modern European music and tonality had become compositionally and aesthetically exhausted, four consecutive radical reactions issued in the following years. These changes are credited not only in expanding the field of music but also the genesis of the practice of sound art: the reintroduction of antique scales by Ravel and Debussy in the late 19th century; Busconi’s subdivision of the 12 semitones of the octave into quarter tones in 1907 (and later picked up by Shostakovich among others); the replacement of music from the consideration of tonal hearing with its consonances and dissonances and the twelve-tone technique, which Schönberg applied after an intermediate phase of free atonality from 1923 onwards. What’s intriguing about this account of music history is the fact that three major changes in music and sound were crafted not aurally but through the reconfiguration of the way we interpret them visually.

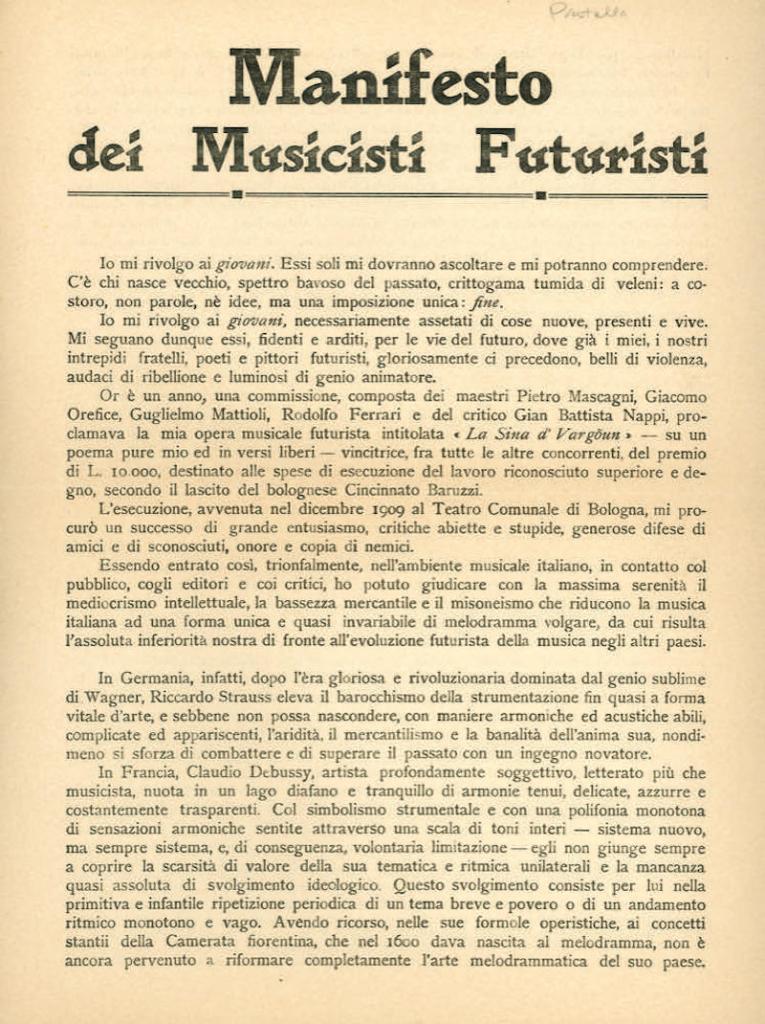

Indeed, the fourth, most radical change was not formulated within music, but within the first provocative-performative avant-garde group of modernism: the Futurists. Luigi Russolo in his 1913 essay “The Sound Art” called for the disruption of all musical systems by integrating noise into music. The idea that the range of music could be extended further inspired a number of musicians, including John Cage, especially in his “Variations I” (1958), to produce every sound imaginable for any number of players, (which Cage called “sound events”). Again, the most significant proponents of this extreme extension of “music” were not composers, but the leading provocative-performative avant-garde artists of the day.

These artists saw precisely the problems and contradictions of the radical extension of music to embrace new and as yet unchartered territory. Russolo wrote in 1913:

“The futurist composer must expand and enrich the range of sounds more and more. … This need and tendency can only be satisfied by the sounds coming to and replacing music. … noise differs from music only in that the vibrations that cause it are confused in time and in intensity, and are irregular. Every noise has a sound, and sometimes a chord, which prevails in the totality of its irregular vibrations.” (Own Translation)

In this philosophy, noises are tuned to sounds and music, avoiding the fundamental break of perception or setting that separates sounds and noises, The term ‘noise’ includes sounds, tones and chords without differentiation and thus implies a common perception with music: a shared way of hearing.

In his essay on the relationship of music and painting, Theodor W. Adorno points to this contradiction, where “the arts merge into one another”. He says that the arts converge only where each one pursues its immanent principle in a pure way. There is a lineage that shows that the pursuit of purity in music has resulted in the branching out of sound art and becoming a discipline in its own right. If we abide by Adorno’s thesis, the advancement of sound art can only mean a merger with other forms of art, including visual arts and forebears in music.

There has been evidence of this since the sixties, from various movements which were very much aware that they had not simply broadened the scope or concept of sound art. These movements had worked with essential categories of art that Modernity had broken off from: the “work of art”, “aesthetic immanence”, “aesthetic attitude”, and even “authorship”. The same can be seen in Jay Ticar’s account of a 1999 exhibit in Surrounded by Water, where he was asked to “submit a sound recording on tape.” Ticar thought of mimicking as abstract gestures the techniques of Disk Jockeying on a Sony mini component. The piece recalls Bruce Naumann’s “6 Day Week – Six Sound Problems” installation of 1968. Naumann made a simple sound everyday that had been recorded in the gallery played from a tape recorder. In both the Naumann and Surrounded by Water exhibition, there was a confrontation with the concept of sound art that can be shown in an art gallery.

Just as paintings and sculptures can not be expanded arbitrarily into objects and installations, sound art requires an aesthetic attitude that supersedes an expansive functional attitude. Sound or music can not simply be enhanced by more sound. Noises are focused on the place and their perceived source of emergence. They belong to the context of functional attitudes that identifies other objects and their location. Sounds and vibrations always refer only to other tones and sounds, within a linguistic musical system.

All sounds, according to Russolo, can be heard as sounds or vibration; and all notes or sounds, according to Duchamp, are in fact noises, energies and realities in the material world. Russolo and Duchamp’s concepts are essential in the face of the incompatible aesthetic and functional attitudes in sound art.

In 1913 Luigi Russolo published the futurist text L’Arte dei Rumori, an illumination on the concept of an extension of music through the inclusion of real sounds of all kinds. In the same year, Marcel Duchamp created a radical random composition with “Erratum Musical” – a score for three voices derived from a procedure of chance composed during New Year’s visit in Rouen in 1913 with his two sisters, Yvonne and Magdeleine, both musicians. They randomly picked up twenty-five notes from a hat ranging from F below middle C up to high F. The notes then were recorded in the score according to the sequence of the drawing. The words that accompanied the music were from a dictionary’s definition of “imprimer” – Faire une empreinte; marquer des traits; une figure sur une surface; imprimer un scau sur cire (To make an imprint; mark with lines; a figure on a surface; impress a seal in wax). With Russolo and Duchamp, sound and chance had entered the sphere of music. Interestingly enough, both Russolo and Duchamp were painters, who figured significantly in the first crisis of modern painting, which involved a reconsideration of representational painting as the dominant mode of painting. Certain central problems of painting practice could be clarified in music: the finiteness of the artistic language or means, or the limitation resulting from its attachment to habitual perceptual or listening habits.

By using the tape recorder (in which a wire was first magnetized in the later thirties), it was possible to record and arrange sounds, and above all to rhythmise them – which was previously only possible in such a way that noises were made in a composed manner, as in the case of Eric Satie. Musique concrète became a term for cutting and mixing recorded sounds to produce music since the late forties. It is a composition method that had a strong suggestive effect – as they referred to noise as indexical and referring to their sources, to objects and movements in the world, as well as to their rhythm.

Since the invention of the synthesizer in the 1960s, electronically generated sounds have become particularly interesting in their capability of being neither sounds or noises; they can be generated without referring to a musical system and without possessing a source (as in noise). They can, so to speak, be cleansed of both music and sound. As soon as electronically produced sound migrated into art and achieved a purity of creation that was previously inconceivable, the field of possible applications of aural phenomena opened up. Artists can now perceive space and even generate space (i.e. the reflection of sound waves in a visualizer), the creation of places by sound sources, imagination of spaces or landscapes through suggestive sounds, wandering noises or sounds, coupling of sounds and the perception of a performing body through sensed vibrations. An interesting prospect that can be seen in Whether you hear it or not is the merging of Zeitkunst and Raumkunst in sound art. This is a milestone for an artform that has all along struggled to distinguish itself from its own history in music. From a concept of sound art that is governed by principles of time, we now have one governed by principles of space.

Leave a comment