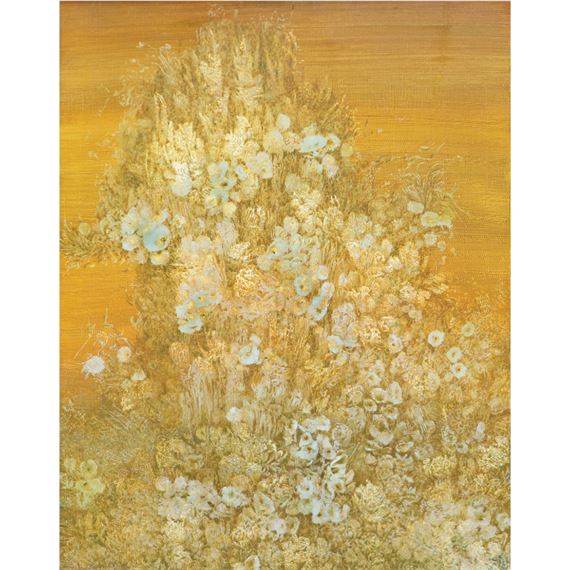

Bouquet Elegant by Juvenal Sansó, c. 1960, ink on paper

Let me begin by telling you the story of how I crossed paths with Sansó. It happened, quite amusingly, two years ago at a group exhibition I organized in an SM Megamall gallery. Sansó happened to be passing by on his way to a different exhibit but saw we had an opening and stopped in. Some of his friends were among our guests. I was too starstruck to approach him—having a National Artist randomly appear at your event is like having the Eraserheads suddenly crash your classroom.

After a few minutes, he left for his original appointment. But later that evening, he returned. As he passed by our glass walls to take another look, he tripped over a wire. Though he quickly regained his balance, I rushed over to help. He smiled, shrugged it off, and let me introduce myself. I offered him cocktails, which he politely declined, saying he had already eaten. But he did compliment our work, his eyes gleaming with warmth and mischief. For a moment, I saw the “Juvenal” in him. It was surreal.

I can’t imagine a better reward for months of effort than those kind words. Considering he had merely stumbled upon our show, and had every reason to be annoyed or tired, his grace and encouragement were remarkable.

A few months later, while organizing a nude sketching session to raise funds for an exhibit, I tried to contact Sansó. I assumed he remembered me from that funny incident and had even told me to remind him of future events. But flattery makes me shy, so I asked Caroline to make the call. She invited him to give the annual art talk at UP and possibly join our sketching session. His first response wasn’t encouraging: “I’m through with nudes,” he quipped. “They don’t excite me anymore.”

We understood. At his age, and with a demanding schedule—he had just finished designing a stage set in Aurora—it was a lot to ask. But he kept talking. Caroline thought it was just courtesy to a student, but it turned out he wanted to discuss the recent controversy over the Order of National Artists. He had strong opinions. He said he didn’t want to serve on the committee anymore if things would continue that way. Ironically, former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo—one of his patrons—had just awarded him the Presidential Medal of Merit, an honor she also gave to Carlo J. Caparas.

Juvenal Sansó was born in Reus, Spain in 1929. He moved with his family to the Philippines as a child. During World War II, while living in Manila, he was injured by shrapnel and reportedly beaten by Japanese soldiers who mistook him for American. After the war, he enrolled at the University of the Philippines School of Fine Arts, where he studied under Fernando Amorsolo.

In contrast to Amorsolo’s genre paintings of rural life and idealized Filipino subjects, Sansó turned to darker themes. His postwar works depicted scenes of urban poverty and psychological trauma. In 1951, he produced a gouache painting titled Incubus, which won First Prize at the Art Association of the Philippines competition. The painting depicts a disfigured blind man in rags, set against a dark background.

Art historian Reuben Cãnete has described Incubus as the first Filipino Expressionist painting in terms of technique and subject matter. It marked a shift away from conventional beauty and idyllic rural scenes. Sansó used distortion, chiaroscuro, and jagged brushwork to render scenes drawn from postwar Manila.

At UP, Sansó had been classmates with Pitoy Moreno—among the last to attend the School of Fine Arts at the Padre Faura campus. A photograph of them with some (then-young) women, now grandmothers, remains in the UP Library archives.

This November, Sansó turns 81—a milestone not just of age, but also of the vast age range of his fans, now quite literally from “1 to 92,” as Sinatra’s Christmas song goes. I count myself among the newer generation of admirers. I became one around the time I began to draw, which, admittedly, was relatively late.

Artists of Sansó’s generation were known for their resilience. Many were artist-intellectuals. I find their writings—including Sansó’s—among the most meaningful texts not just in the study of art, but in human experience itself. Sansó could relate complex ideas to just about anyone, even self-confessed philistines, while continuing to push the visual and conceptual limits of his chosen subjects. I sometimes worry we’re becoming the opposite kind of artist—the one with no public beyond a small coterie, operating “above” tradition rather than within it. In doing so, we risk leaving the public behind, like followers of some distant Pied Piper.

Of all the elements in his paintings, I find color to be the most powerful—through it, we glimpse what makes his work distinctly Filipino.

When I first tried to write about him, I was warned by other writers not to lean too heavily on textbook explanations of his work. But so much can already be said just by observing how he uses color.

Golden Bouquet, 1960

In Bouquet on Gold, for example, the floral subject is ostensibly simple—roses and chrysanthemums in bloom—but the background shimmers in a gilded flatness that resists depth. The flowers, rendered in impossible jewel tones, seem to levitate rather than rest. Their stems taper off without anchors. Here, Sansó is less interested in representing botanical accuracy than in eliciting the emotional resonance of a fleeting moment between joy and mourning.

I was introduced to Sansó’s work by my father—who, I should note, is not an artist, a critic, or a collector. He happened upon a Sansó exhibit at a hotel in Manila and couldn’t stop marveling at the paintings. And I marveled that he was marveling. He rarely talks about art. In fact, he has only one other art-related story: he once passed on the chance to buy a Joya painting for a thousand pesos in the 1970s.

But that’s another story. Still, it’s proof that I knew of Sansó—his name and reputation—long before I ever saw his paintings in person. I often think of Sancho Panza from Don Quixote when I read his name (I later learned the Sansós were actually a family of knights). My earliest encounters with his paintings were through glossy catalogues—particularly Art Philippines by Manuel Duldulao, and a volume simply titled Sansó by Alejandro Roces. A few pieces caught my eye right away, but it wasn’t until I saw them in person that I truly became captivated.

“The Joy of Dawn”(Brittany Coast Series), 11.75 x 17.75 inches, acrylic

“The Joy of Dawn”(Brittany Coast Series), 11.75 x 17.75 inches, acrylic

In his Brittany Coast series, Sansó conjures seaside villages with dreamlike precision. There’s something unreal about the textures—rock walls that glint like velvet, skies saturated in spectral mauves and greens. These paintings aren’t documentary. They are psychological interiors, mapping memory onto landscape. The coast, for Sansó, becomes a metaphor for distance and loss: it is where the self meets its longing.

Juvenal Sanso, “Lueurs,” 1963, etching and aquatint, signed in pencil lower right, edition of 260, printed by G. LeBlanc & Cie, Paris, the Print Cub of Cleveland edition no. 41 for 1963, matted and framed.

In 1951, Sansó traveled to Europe and eventually settled in Paris, where he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts. Between 1953 and 1957, he produced what became known as his Dark Series. These works were primarily executed in black and white using ink, tempera, oil, and printmaking techniques.

Sansó’s subjects during this period included Parisian street figures, cabaret performers, and marginalized characters. The portraits were exaggerated caricatures rendered in stark lines and aggressive brushstrokes. The compositions featured distorted anatomy, heavy shading, and emotional intensity. One example is Window Shopping (1956), which shows an emaciated man gazing at luxury goods through a store window.

Sansó’s Paris works were noted for their satirical and grotesque qualities. Critics have compared them to the works of Francisco Goya and James Ensor. Many of the pieces display a macabre sense of humor and thematic references to alienation and postwar trauma. A recurring motif in this period was the bouquet, reimagined as an assemblage of distorted human heads, as seen in Bouquet (Elegant) (1960s), where floral forms are rendered as grotesque facial features using black ink.

These works were not commercially successful during their time. Sansó’s debut solo exhibition in Paris in 1956 reportedly sold no works. However, in later years, the Dark Series gained recognition for their originality and expressive intensity. Sansó later described this period as a necessary catharsis.

By the late 1950s, he began spending summers in Brittany, France, where the coastal landscapes influenced a transition in his art. His palette lightened, and his compositions shifted toward romantic and lyrical representations of nature. Critics and curators have suggested that these later, colorful works would not have been possible without the earlier expressionist explorations.

Sansó’s Dark Period remains a significant body of work in mid-20th century Philippine art history but has not been discussed to the fullest extent. It set him apart from contemporaries such as Amorsolo, who emphasized rural beauty, and from abstract artists such as Fernando Zóbel and José Joya. Sansó’s early paintings brought a psychological and narrative depth to postwar Filipino modernism, marking a pivotal turn in the representation of trauma and emotion in Southeast Asian art.

Sansó is international in two senses: by birth, and by accomplishment. He was never destined to be just another painter of flowers—though when he did paint them, they always felt like more than just decoration. Later in life, he credited his childhood journey to Manila as formative to his art.

In Sansó by Sansó, he recalls:

“The next encounter with water was a long trip by boat from Barcelona to Manila. It figured as a major event in my life because for forty days and nights I was awakened to the vastness and infiniteness of the sea aboard the Norwegian steamship, Torrens.”

In Manila, they lived beside the Pasig River, where he learned to swim—and once saved two girls from drowning. His earliest memories were here in the Philippines. His recollections of Catalonia, meanwhile, were mostly secondhand, through old photos.

They fled Spain in 1934. Civil war loomed. And what they ran from in Europe—violence, chaos—they would face again during World War II. Sansó survived a bombing in Sta. Ana thanks to a Filipino stranger who pulled him from the rubble. He even worked as a bus conductor during the war.

He enrolled at UP as a special student under Fernando Amorsolo, then later attended UST.

Diplomate, hand signed (lower right), copperplate etching on paper, 11/50, 20 cm x 15 cm

His early paintings from the 1940s and 1950s, some featured in his recent exhibitions, are elegant and well-executed—but still formal exercises, standard plates of the time. His real breakthrough came later, after the return of modernists like Joya and Abueva. That lull in the 1950s—UP’s “Age of Innocence,” with its hayrides and carnivals—was reflected in the art of the time. But in Sansó’s work, you could already see the flickers of something else. A lightness, a consistency. A playfulness with purpose. In his own words: makulit.

You cannot contain Sansó in any single movement. The label “Pioneer of Expressionism” feels inaccurate. If expressionism means the German movement, Sansó was half a century late and geographically off. If we mean Filipino expressionism, its earliest pioneers were long forgotten. Sansó defies categorization. To confine him with labels is to miss the point.

Take his seascapes and florals—subjects often dismissed as decorative. Yet in his hands, they hint at something deeper. His seascapes are metaphors for both enclosure and alienation. His flowers, paradoxes of death and beauty. Why must beautiful things fade so quickly?

Yes, he’s an expressionist—but only if we take the term in its original spirit: a way of distorting reality to express inner emotion. His art is deeply subjective, charged with mood, and evocative of what it means to be alive.

Insisting too strongly on his being “Filipino” risks flattening his complexity. He is many things at once. To reduce him is to miss the multiplicity of voices and visions his paintings offer.

Leave a comment